Arlington resident Garrett Peck is a nonfiction author, a self-described “history dork,” and — apparently — quite the booze enthusiast.

Arlington resident Garrett Peck is a nonfiction author, a self-described “history dork,” and — apparently — quite the booze enthusiast.

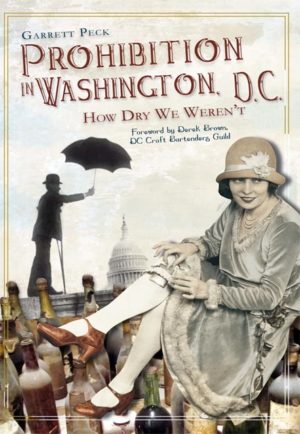

Following up on his book The Prohibition Hangover: Alcohol in America, Peck has just released “Prohibition in Washington, D.C.: How Dry We Weren’t.” The book chronicles the history of temperance, vice and law enforcement in the Nation’s Capital from about 1917 t0 1934. The book includes dozens of historic images and even contains 11 vintage cocktail recipes.

Peck will be participating in an author talk and book signing at Arlington Central Library (1015 N. Quincy Street) starting at 7:00 p.m. on Thursday, June 9. We asked him to tell us a bit about the role Arlington played in the history of prohibition. Turns out we were the place where D.C. dumped some of its contraband beer.

“As you probably know, Arlington wasn’t heavily settled yet during the era of national Prohibition (1920-1933), though it certainly was growing: the neighborhoods along the streetcar line between Clarendon and Georgetown grew up as leafy suburbs during this period.

“As you probably know, Arlington wasn’t heavily settled yet during the era of national Prohibition (1920-1933), though it certainly was growing: the neighborhoods along the streetcar line between Clarendon and Georgetown grew up as leafy suburbs during this period.

Virginia actually started Prohibition earlier than national Prohibition: we went dry in 1916. This closed down all the breweries and distilleries in the state – including the Arlington Brewing Company that was just over the Key Bridge from Georgetown, where the Key Bridge Marriott is now in Rosslyn. Rosslyn at the time was a bit of an industrial zone, as an offshoot from the C&O Canal crossed the river to connect to Alexandria, and there was a rail yard, lumber yard, a Noland Plumbing factory, and of course the brewery. (There’s a great aerial photo of Rosslyn from 1930 in James Goode’s book “Capital Losses”; you can clearly see the Arlington Brewing Co. building, which at the time was producing Cherry Smash, a non-alcohol beverage). Another brewery – the Robert Portner Brewing Company in Alexandria, which was one of the largest breweries in the South, was also closed. Congress declared Washington, DC to be dry on November 1, 1917, and the remaining four breweries in DC all stopped their brewing operations. Only one survived Prohibition: the Christian Heurich Brewing Company, which was where the Kennedy Center now is, and operated until 1956.

Though Virginia was technically dry, people still kept producing illegal alcohol – especially distilled spirits (“bathtub gin” and moonshine) in homemade stills. Or alcohol could be smuggled in by ship to Alexandria, then offloaded and distributed into the District. One of the key arteries was the 14th Street Bridge; bootleggers often brought cargoes of liquor from Arlington and Alexandria into the city, where they could sell it. The local police would sometimes tip off the DC Metropolitan Police Department. One such incident occurred on January 21, 1922, when the MPD’s flying squadron was waiting at the bridge for a shipment to arrive. The bootleggers crashed into the squad car, then proceeded up 14th Street and through the city as the police gave chase, firing their guns as the sidewalks were full of people out on their lunch hour. Several people were injured as the bootleggers desperately careened onto the sidewalks. Their car finally hit a coal truck at 5th and O Streets, NW, and the chase came to an end.

Though Virginia was technically dry, people still kept producing illegal alcohol – especially distilled spirits (“bathtub gin” and moonshine) in homemade stills. Or alcohol could be smuggled in by ship to Alexandria, then offloaded and distributed into the District. One of the key arteries was the 14th Street Bridge; bootleggers often brought cargoes of liquor from Arlington and Alexandria into the city, where they could sell it. The local police would sometimes tip off the DC Metropolitan Police Department. One such incident occurred on January 21, 1922, when the MPD’s flying squadron was waiting at the bridge for a shipment to arrive. The bootleggers crashed into the squad car, then proceeded up 14th Street and through the city as the police gave chase, firing their guns as the sidewalks were full of people out on their lunch hour. Several people were injured as the bootleggers desperately careened onto the sidewalks. Their car finally hit a coal truck at 5th and O Streets, NW, and the chase came to an end.

Arlington was also a place where Washington dumped some of its trash. In 1923, Prohibition Bureau agents seized 749 cases of beer that were being transported from a Philadelphia brewery to DC. The judge overseeing the case ordered that the beer be destroyed. Agents smashed 18,000 bottles of beer – one at a time – in the Arlington dump in November 1923.”

(Photos from Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division via Garrett Peck)