This weekend the League of Women Voters of Arlington is hosting a workshop to educate residents about the history of racism behind American — and Arlington’s — housing policies.

The free workshop is co-sponsored by the local NAACP branch and the nonprofit Alliance for Housing Solutions, and will run from 1-3 p.m. this Saturday, September 28 at Wakefield High School.

Local nonprofit Challenging Racism will explain how the federal government denied black homebuyers mortgages — a policy known as redlining — and subsidized white suburbs.

Former Wakefield teacher and co-founder of Challenging Racism, Marty Swaim, told ARLnow that the Federal Housing Administration started subsidized mortgages during the Great Depression — but only to whites. In segregated Arlington, this led to developers building suburbs for white buyers who could access the federal program helping them afford the properties.

“It depressed the value of black properties because it made those areas even less desirable,” Swaim said. “It’s a cascade of effects.”

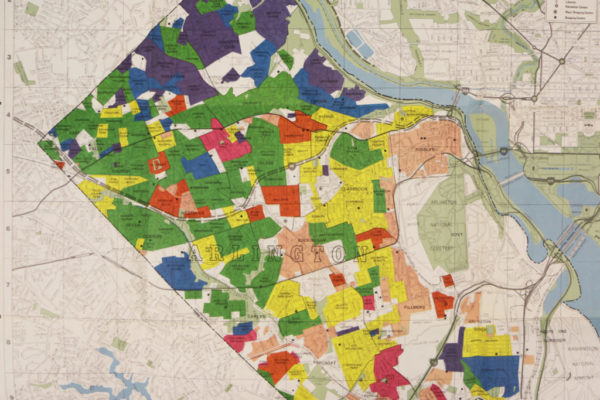

One 1971 HUD guide for homebuyers in Arlington, retrieved from the Center of Local History’s archives, mapped housing by price. Black neighborhoods like Hall’s Hill and Green Valley were color-coded in red to signify the lowest home values (under $20,000.) Whiter neighborhoods in North Arlington were shaded blue and purple to indicate more attractive homes valued between $40,000 and $50,000.

“A lot of Federal Housing Administration loans went to people who settled in these areas, and they were all white,” said Swaim.

Redlining was in addition to another form of discrimination prevalent in Virginia: restrictive covenants on deeds that prevented homeowners from selling to minority homebuyers. Some such covenants remain on deeds in Arlington, unenforceable but a reminder of the state’s segregated past.

Redlining and restrictive covenants were outlawed in 1968 with the passage of the Fair Housing Act, a bill which took years to gain traction. In 1965, activists in Northern Virginia led a petition drive to support it, garnering signatures from 9,926 Arlingtonians, some of whom reporters from the Arlington Sun described as signing the petition in secret from their husbands or neighbors.

“It is abundantly clear that the Negroes will be welcomed in hundreds of neighborhoods in Northern Virginia,” activist Arthur Hughes told the Sun at the time.

But even after the Fair Housing Act passed, decades of discrimination would affect black neighborhoods in Arlington, and nationwide, for years to come.

“Arlington is not immune,” agreed Carol Brooke, who heads the League’s Affordable Housing Committee.

Brooke said Saturday’s event is an opportunity to highlight how racist policies shaped neighborhoods and determined who has been allowed to call Arlington home.

One example she cited is the the county’s use of zoning to create and preserve single-family homes — a policy researcher Richard Rothstein has linked to communities trying to price out black neighbors. This year, it’s also a policy lawmakers from Charlotte to Minneapolis to Oregon are abolishing or weakening.

In 1975, County Board Chair John Purdy wrote a letter warning officials to keep watch on banks and real estate agents not following the fair housing laws.

Not long after, a county task force found that when black homebuyers had enough money to purchase more expensive homes, real estate agents “steered” them to only South Arlington properties, according to a copy of the report ARLnow found in the history center’s archives. The same investigation found black homebuyers needed higher levels of income to qualify for the same properties as the undercover white homebuyers.

In 1990, the Washington Post reported a study finding that black homebuyers in Arlington were treated “significantly different” than their white counterparts 10 percent of the time, with real estate agents “steering” clients in the same way the 1970s report had found.

“We are interested in having people being to think about how institutional racism developed in Arlington,” said Swaim, who said she co-founded Challenging Racism after learning about the persistent racial achievement gaps in Arlington Public Schools. When researching the issue, she learned unequal school performance was of a wider legacy of racist policies.

“Those conversations are intended to move you past the ‘getting started phase’ so you have some skills and a lot of content knowledge, and can take some leadership to end racism,” she said of Saturday’s event.

Brooke said the League is also hoping the workshop can help lead to better conversations, and possibility solutions, to the county’s affordable housing shortage that some forecast could displace 20,000 residents.

“The goal is enlightenment and advocacy to help change the housing patterns that still exist that are still the legacy of those racist practice,” she said.

Although the workshop’s online signup is sold out, she expects some last-minute cancellations and encourages people interested in attending to still stop by.