Lyon’s Legacy is a limited-run opinion column on the history of housing in Arlington. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

A century ago, white supremacy in Arlington was bigger than Frank Lyon. It reached up into the County Board, down into secret societies, and so deeply into our county’s life that its fingerprints are still found in our elections, our zoning laws, and traces hiding in our rafters and backyards.

This is the fifth part of Lyon’s Legacy, a biweekly series on ARLnow (you can read the whole thing, with citations, here). It will tell an eight-part history of how Black people, and other groups that experience racial or economic discrimination, have been excluded from living in Arlington County.

Last time, we saw how Frank Lyon and other private developers used three strategies to keep Black people out of their new neighborhoods: racially-restrictive covenants, economically-exclusive zoning, and automobile-oriented design. This week, we’ll see how Arlington’s government — like governments across the country — adopted these techniques of segregation and imposed them everywhere.

Lyon wasn’t alone in wanting an all-white Arlington. In 1912 the County Board passed a segregation act preventing the sale of houses to Black people in all new developments. The law was in effect for five years until a 1917 Supreme Court decision nullified such government-imposed segregation policies across the nation. But private restrictive covenants like those used by Lyon, on individual homes and neighborhoods, weren’t made illegal for another few decades.

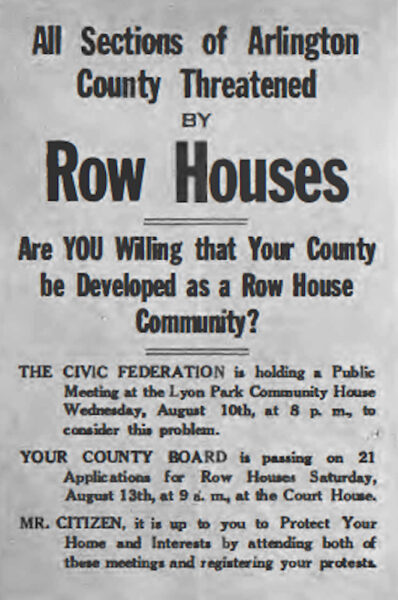

The County Board’s first attempt to keep Black people out of Arlington was vexed by the Supreme Court. But they didn’t give up. The Board adapted Lyon’s technique of exclusivity through expense into Arlington’s first-ever county-wide zoning code in 1930.

Almost the entire county was zoned exclusively for single-family detached houses. The code made it illegal to build apartments, rowhouses, duplexes, or stacked flats across Arlington. This ban kept poor people out of new suburbs and it arrested the growth of existing Black communities, most of which already had the middle-density housing that the zoning code forbade. Unlike the restrictive covenants, which were nullified decades ago, this economically-exclusive zoning remains in effect on almost three-quarters of our county.

Exclusive zoning was motivated, in part if not entirely, by white supremacy. The same zoning code also enabled the construction of a racial segregation wall to separate Hall’s Hill, which was Black, from the white neighborhoods of Fostoria and Waycroft. Parts of this wall still stand today, though many of the remains were toppled in 2019’s July flash flood. One of the code’s authors, Edward Duncan, helped to write the 1912 segregation law. The 1930 zoning code was not racist in its language, but it was racist in its intent and its impacts.

Arlington wasn’t uniquely racist. The story was familiar across the country.

Legal historian Richard Rothstein shows: “…there was also enough open racial intent behind exclusionary zoning that it is integral to the story of de jure [legal] segregation. Such economic zoning was rare in the United States before World War I, but the Buchanan decision [by the Supreme Court to ban explicit segregation] provoked urgent interest in zoning as a way to circumvent the ruling.”

Still today, in many major American cities, as much as 90% of residential land is zoned exclusively for single-family detached houses.

Nor was the zoning code the only county-wide racist policy that Arlington witnessed in 1930. In the beginning of that year, four members of Arlington’s Black community offered their candidacy for County Board. At the time, that body’s seats were determined on the basis of district, unlike our at-large elections today.

In the light of Arlington’s geographic segregation, the district voting system meant that a Black candidate actually had a shot at winning. For white Arlingtonians, this was unacceptable.

As George Vollin, a Black Arlingtonian alive at the time, testified decades later: “…it was only after it became known that Blacks intended to run for elective office that delegations from the White community traveled to Richmond and appeared before the legislature urging the new law described above to permit a vote on changing the government form to include the election of governing body members at-large instead of by several single member districts.” None of the four candidates won, and the county didn’t see a Black member of the Board until the 1980s. Just like economically-exclusive zoning, we still use the at-large system today.

In the decades after Lyon began work on his developments, Arlington transformed from a rural county to a built-out suburb. And although Lyon and his League were among the first to use these racially-exclusive tactics, they were not the last. Not just in Northern Virginia, but across the nation: as suburbs sprawled over the course of the 20th century, lot sizes got bigger and bigger, roads got more and more winding, and ‘white flight’ to these exclusive new developments meant that poorer families, many Black, were abandoned to the dwindling tax bases of central cities.

Lyon might have been racist in his private beliefs or he might not have — there’s no record of his thoughts one way or the other. Ultimately it doesn’t matter much: in either case he used white supremacy to shape Arlington to his ends. But some Arlingtonians of his time were racist in every way.

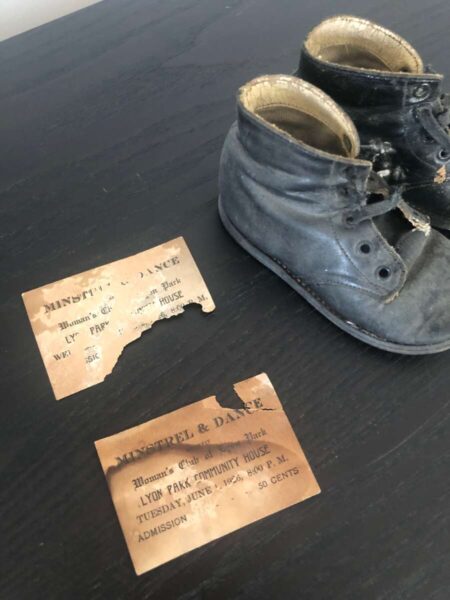

The K.K.K. was active in our county throughout the 1920s. In 1922, they held a parade in Cherrydale. On April 16, 1926, more than 100 members of the Ballston Ku Klux Klavern raised a flag over Lyon Park and stormed into a Parent Teachers Association meeting at the neighborhood elementary school.

Klan activity wasn’t just for show. It affected the outcome of at least one Arlington election. The Washington Tribune of 1927 reported that Black votes were key to the election of that year, and that “[t]he Negro voters resented the intermeddling in Arlington county politics by Crandall Mackey, and his raising of the Ku Klux Klan as a bugaboo to scare Negroes into supporting his candidates.”

Frank Lyon wanted an exclusive, profitable, white community. By using racially-restrictive covenants, economically-exclusive zoning, and car-oriented planning, he got what he wanted.

A local historian, Ruth Rose, has written: “Today, the lovely communities of Lyon Park and Lyon Village reflect the way of life which Frank Lyon must have envisioned when he started developing those communities many years ago.” The rest of the county, region, and nation did all they could to use the same tactics.

Author’s note: The third article in this series made a few factual errors. First, Crandal Mackey did not in fact attend the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1901-1902; rather, he attended the Virginia Gubernatorial Convention of 1901. Frank Lyon attended the Constitutional Convention as Clerk / stenographer, not as a voting representative. Second, Mackey’s raid was not only on Rosslyn, but also on Jackson City, a similar community containing many non-segregated saloons located near today’s Pentagon City. Third, Mackey did not ‘batter down the door’ to Heath’s Place, but rather encountered Eddie Heath there, who was wielding a shotgun, and disarmed him. My apologies for these errors and my gratitude to a reader for pointing them out.