Lyon’s Legacy is a limited-run opinion column on the history of housing in Arlington. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

“IN THIS early-twentieth-century era, when African Americans in the South faced terror that maintained them in subjugation, when African Americans throughout the nation were being driven from small towns where they had previously enjoyed a measure of integration and safety, and when the federal government had abandoned its African American civil servants, we should not be surprised to learn that there was a new dedication on the part of public officials to ensure that white families’ homes would be removed from proximity to African Americans in large urban areas.”

Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law

A century ago, Robert E. Lee defeated both George Washington and Pocahontas. The contest? A decision to rename the county today known as Arlington.

In 1919, this was Alexandria County. But it was growing. The county was tired of being confused with Alexandria City to its south. So the Civic Federation held a contest to choose a new name, and “Arlington,” the name of Robert E. Lee’s personal mansion, won out over our nation’s first president and one of its most mythologized Native inhabitants.

This is the fourth part of Lyon’s Legacy, a biweekly series (you can read the whole thing, with citations, here). It will tell an eight-part history of how Black people, and other groups that experience racial or economic discrimination, have been excluded from living in Arlington County. Last week, the story told how Frank Lyon and his allies built their power in our county. This week we’ll see what they did with it.

Arlington’s new symbol was a good one to represent the new county that men like Frank Lyon were building. Lee fought for white supremacy just decades earlier, and the Union army drove him out of his home. Now Lyon led the county’s developers and planners to create a new Arlington. Frank Lyon, by pen and by brick, would succeed where Lee by sword had failed. The developers and planners of Lyon’s day embeded white supremacy so deeply in the foundation of our county that it has not yet today been driven out.

The raid in Rosslyn was a turning point. Shortly after that day, Lyon claimed a stake in the county’s land values: he became a real-estate developer. First, he joined a colleague to build a few blocks of houses in Clarendon; then he bought out that colleague’s share of the business and built a few more. But it wasn’t until 1919, the year of the county’s renaming, that Lyon really got going. That year he broke ground on Lyon Park. Four years later he began Lyon Village. Today those neighborhoods hold about 3,500 houses. Lyon’s partners in the Good Citizen’s League built many other neighborhoods: Maywood, for example, was largely organized by Crandall Mackey. By the time Lyon was done, nearly three percent of all the land in Arlington County had passed through his personal hands.

Frank Lyon, like other white developers and legislators of the time, did all he could to keep Black people out of Arlington. Lyon used three methods to this end: restrictive covenants, exclusive zoning, and automobile-oriented design.

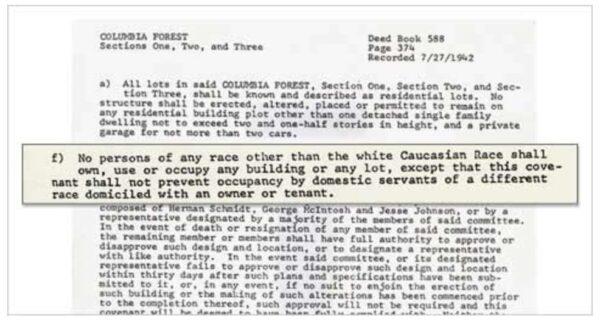

Lyon’s first technique was blunt. Whenever he sold land, Frank Lyon made a binding contract with the buyer that they would never sell or lease the land to Black people or to any other non-whites. The legal agreement remained with the property, so that no Black person would ever be able to live on the land except as a servant. This type of contract was called a “restrictive covenant,” and it was the most explicit weapon in Lyon’s arsenal.

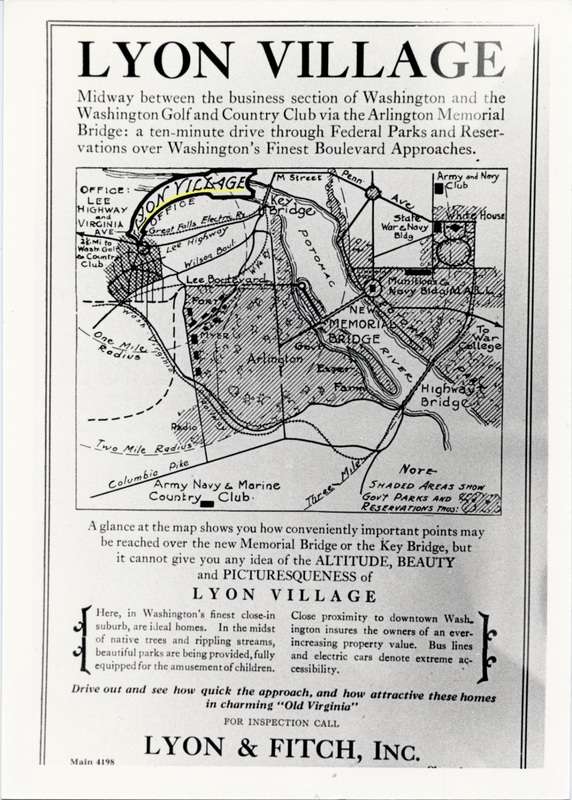

One such covenant mandates that “neither said property nor any part thereof nor any interest therein shall be sold or leased to any one not of the Caucasian race.” Racism even became a selling point. Lyon Village was advertised under the claim that it was “reserved for the white race alone.”

The second technique was pragmatic: Like many developers of his time, Frank Lyon made sure his houses would be expensive.

To accomplish this, he designated unusually large lots (at least 50 feet wide), meaning that any buyer would have to pay the price of that expanse. A lot in one of Lyon’s developments cost up to ten times as much as one in a nearby Black neighborhood. Lyon even stipulated in his deeds that “…nor shall any house costing less than $2,000, other than an outbuilding, be erected thereon.” Frank Lyon knew that Black people were often denied well-paid employment in Washington and Virginia (as well as being denied bank loans for homeownership), and he knew that they would rarely be able to afford homes at such expense.

Certainly some Black people in the 1920s were wealthy and could have afforded Lyon’s homes if not for the restrictive covenants, but, on the whole, Black people tended to be poorer, and economically-exclusive zoning was effective at keeping poor people of all races out of these new neighborhoods.

Lyon’s third strategy was his subtlest. Laws can be changed, nullifying covenants or rewriting codes. But once a street is built, its path cannot be altered but with great effort. And when Frank Lyon built Lyon Village, he embedded racism in its very streets.

Lyon Village was Arlington’s first development on streets that were designed with cars, rather than pedestrians, in mind. It was the first to advertise its proximity to Washington by highways rather than by streetcars. It was the first place in Arlington to have winding roads. Winding roads may be pleasant driving or nice for a stroll, but their curves make them less efficient for people walking to get somewhere.

Large lot sizes also reduced urban density, pushing things farther apart and making them harder to walk to. Because people riding buses or trains need to walk from their homes to the station, Lyon Village’s very design makes it difficult to access by public transit. Owning a car is expensive. Because Frank Lyon designed Lyon Village for cars rather than pedestrians, he designed Lyon Village for the wealthy rather than the poor.

D. Taylor Reich is a native of Arlington and a graduate of H-B Woodlawn. They work as a researcher in urban mobility analytics with the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, where their research has been covered by international publications including The Guardian, BBC, and China Daily. Previously, they were a Fulbright scholar in Amman, Jordan. Taylor has served on the Arlington Transportation Commission and the Plan Lee Highway Community Forum.