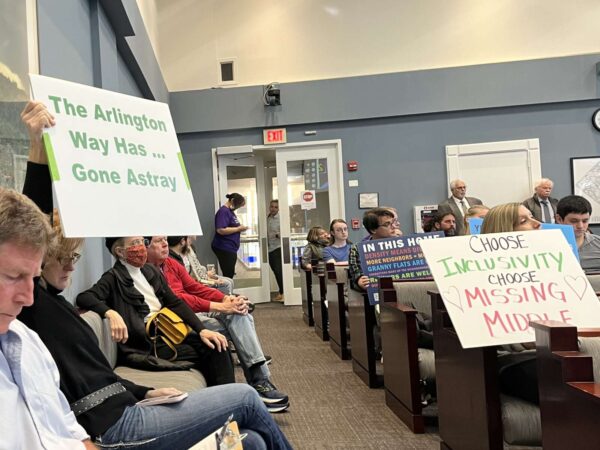

Arlington spent $74,000 in two months combating a lawsuit over Missing Middle housing, public records show, drawing the ire of a County Board candidate.

The county, which hired law firm Gentry Locke at the start of this year, paid $49,251 for services in January and $24,536 in February, according to invoices. Meanwhile, a GoFundMe campaign for the lawsuit — which alleges that Arlington failed to adequately study the impacts of Missing Middle before approving the zoning change — has raised about $69,000 since last June.