(Updated at 4:10 p.m.) There was one question that ran through the mind of Zeb Armstrong, a newlywed from South Carolina recently drafted for service in the Vietnam War.

“Will I return?”

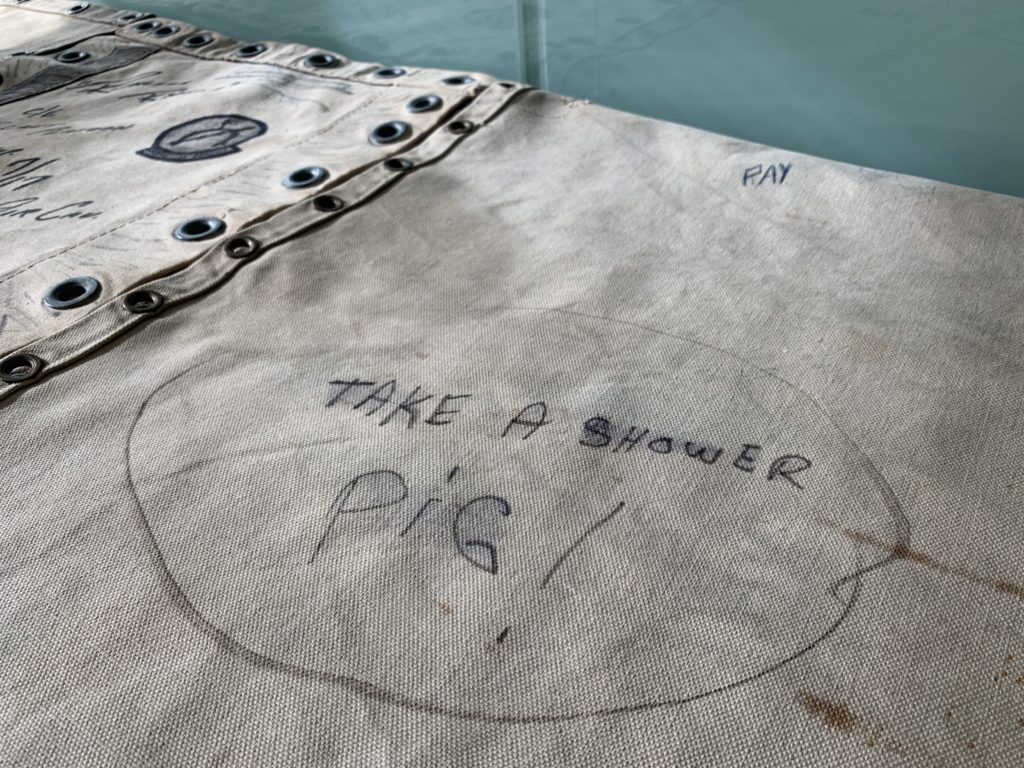

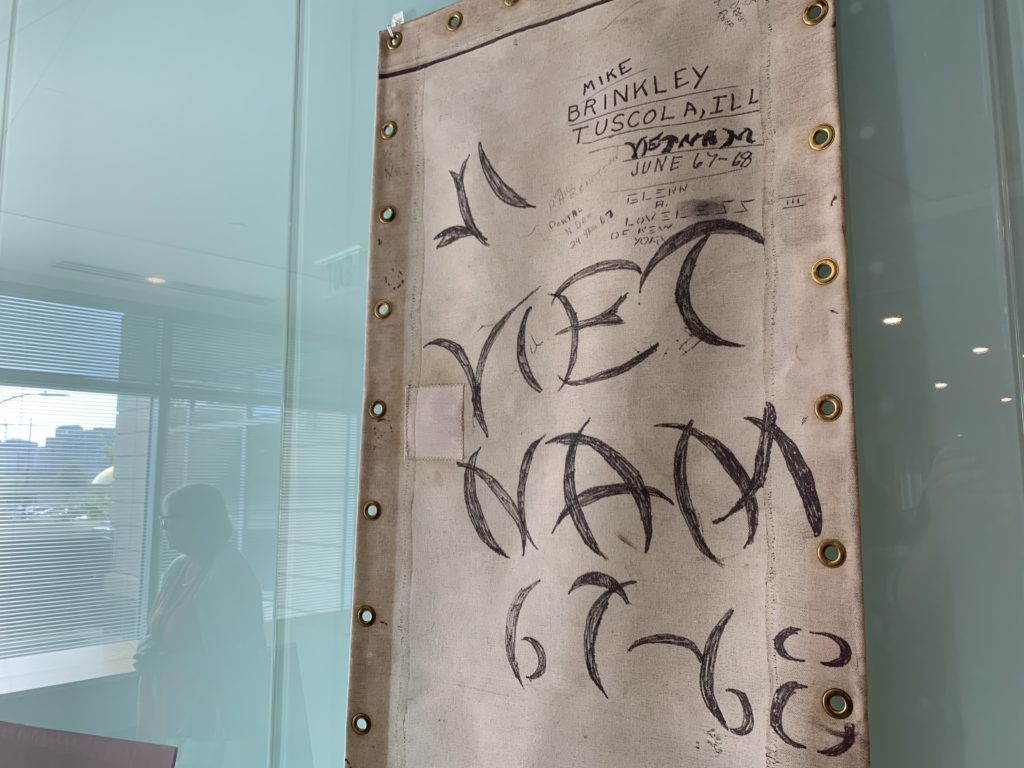

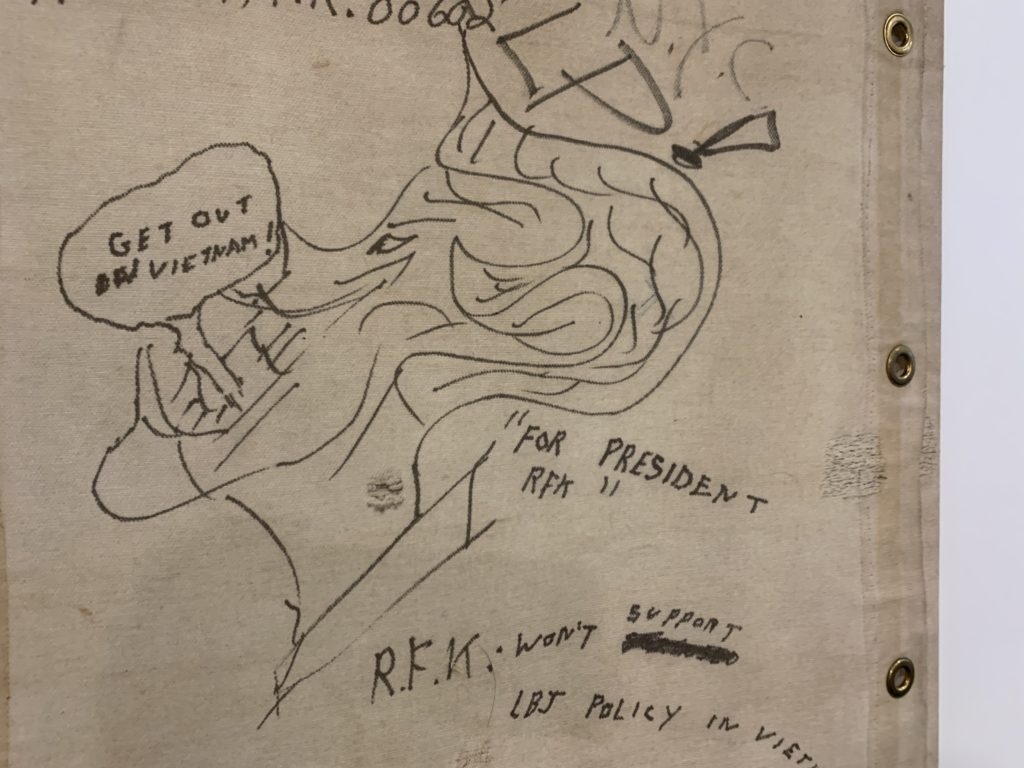

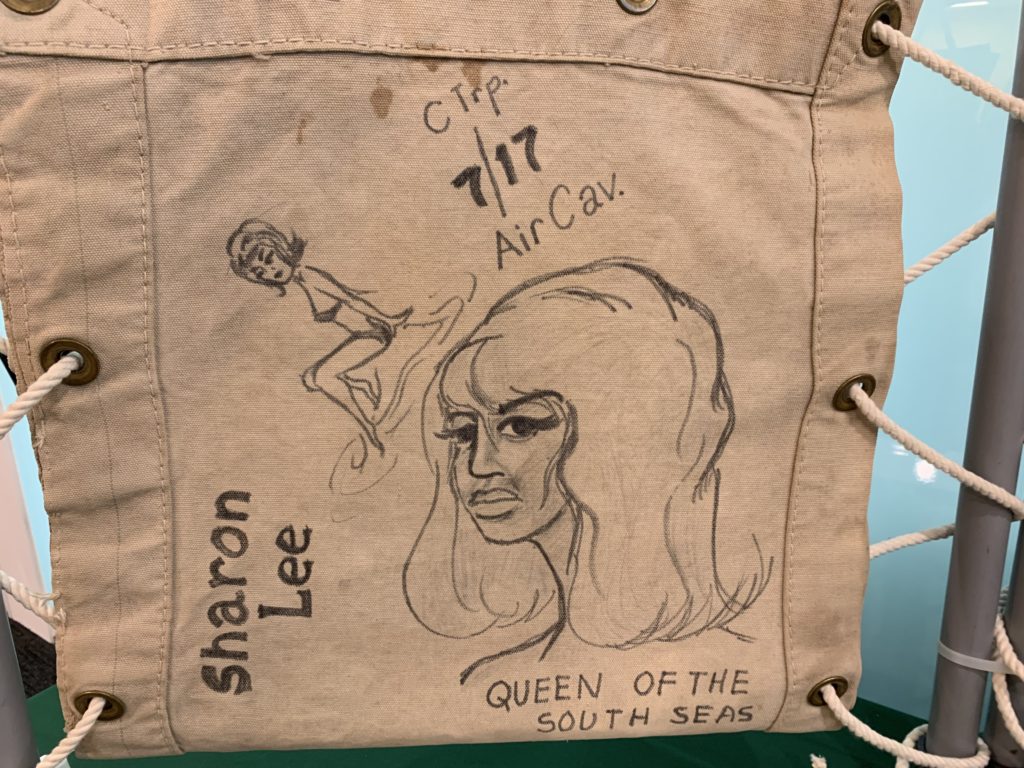

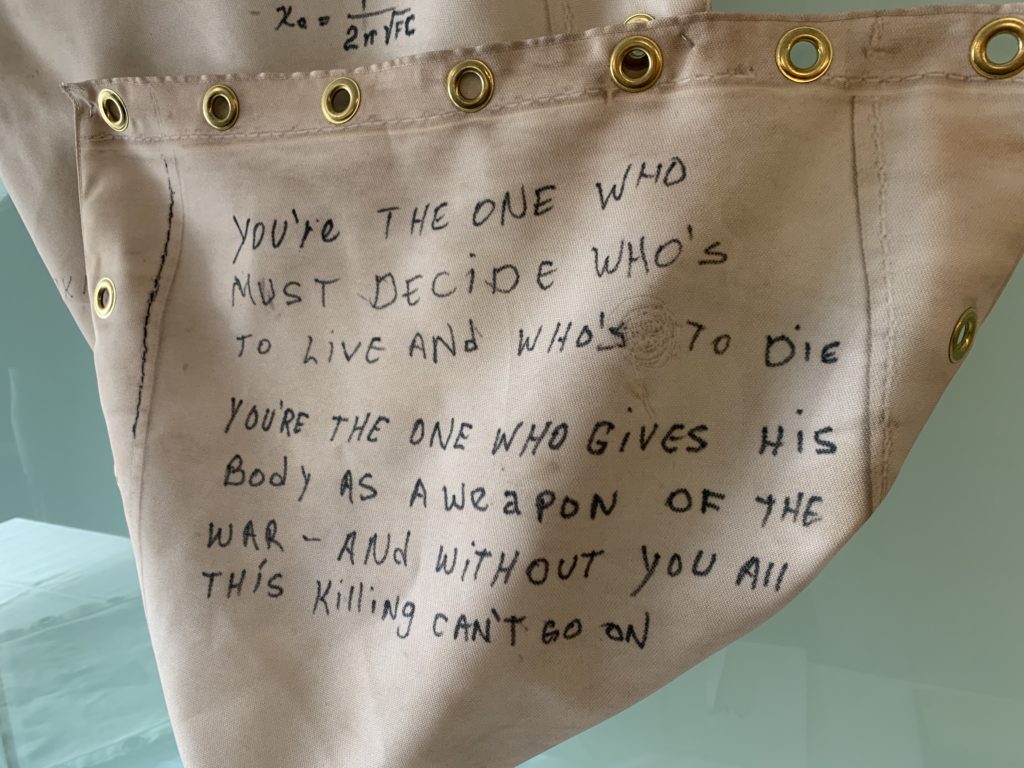

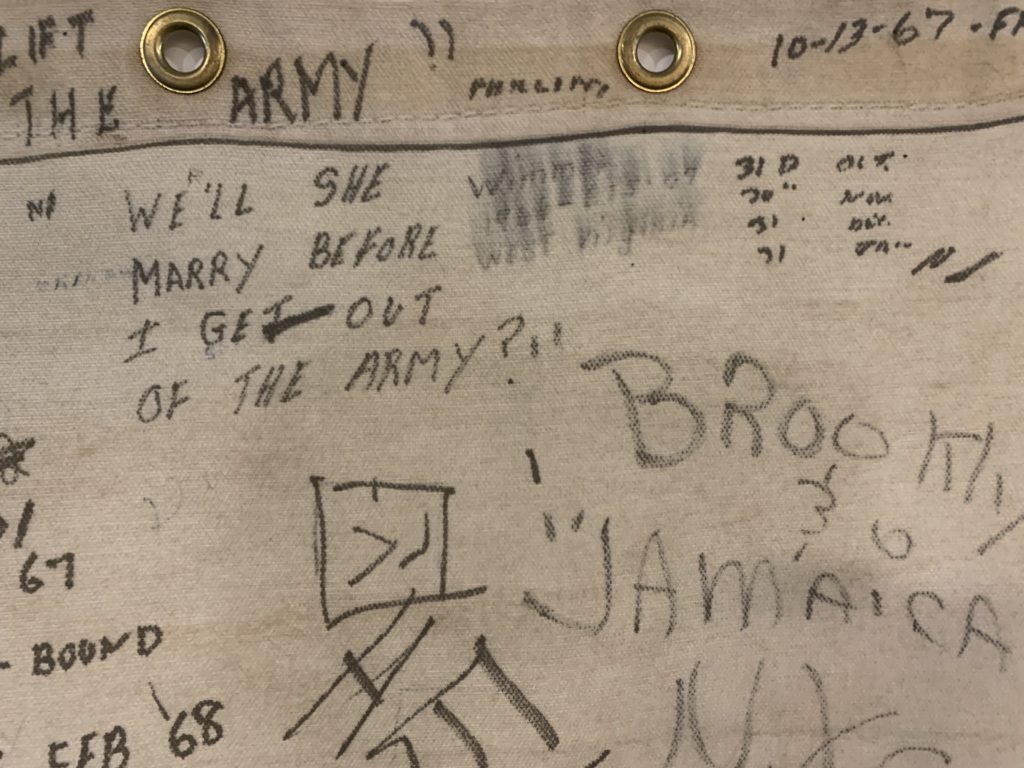

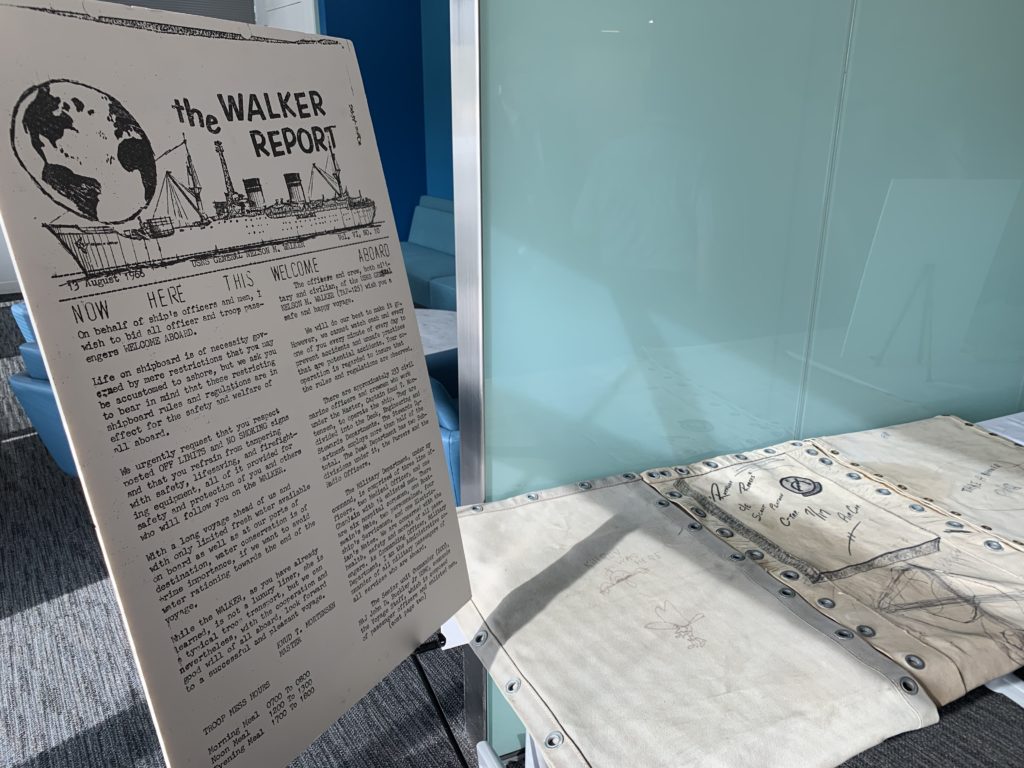

It was a question Armstrong etched onto his bunk in a magic marker, alongside hundreds of other messages and images from countless young men taking a journey many wouldn’t return from. The 18-21 day trip from the West Coast to Vietnam aboard the USNS General Nelson Walker left a lot of time for soldiers to get homesick or anxious about the journey ahead. Though against regulations, drawing on the canvas beds became a widespread past-time.

Yesterday (Tuesday), a traveling exhibit called the Vietnam Graffiti Project stopped at CNA, a nonprofit research and analysis organization in Clarendon that works on improving efficiency and effectiveness of military operations. For one day, canvases covered with years of doodling from soldiers covered the walls of the offices, and co-founder Art Beltrone spoke with CNA personnel about their stories.

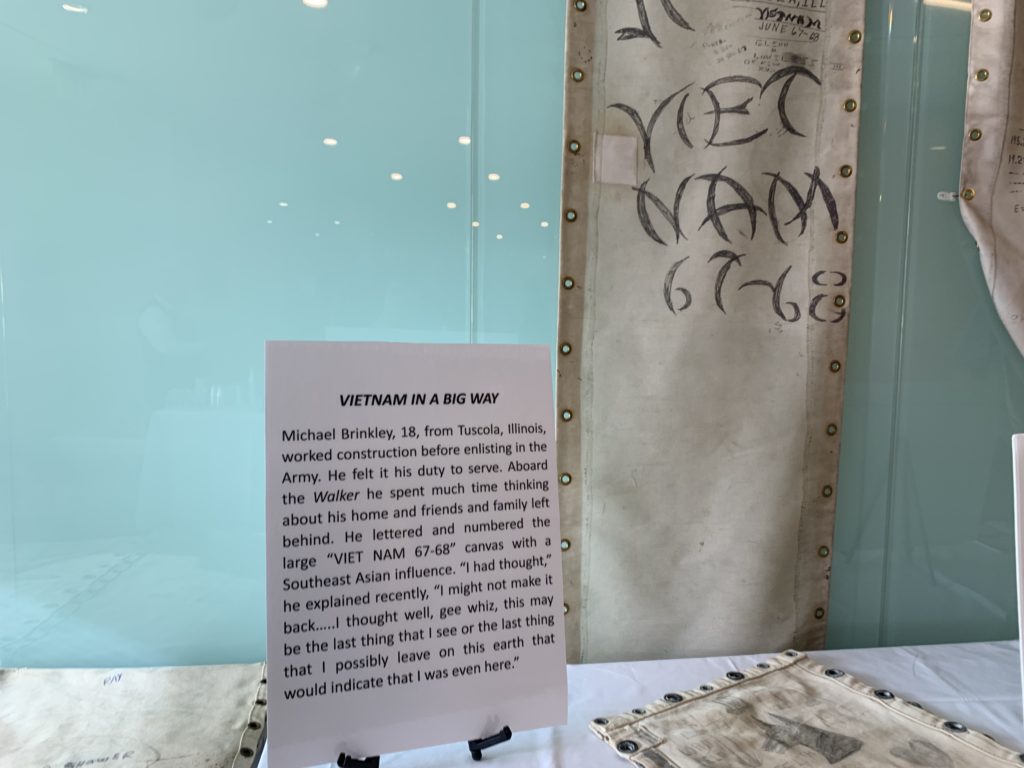

The ship started its service in the final days of WWII then ferried troops to and from the Korean War and the Vietnam War. After Vietnam, the ship was put into the James River Reserve fleet — the Ghost Fleet — to be reactivated in case of an emergency. It sat there virtually untouched until Beltrone visited the ship with Jack Fisk — a production designer doing research for The Thin Red Line — and stumbled on rooms littered with relics from the war sitting exactly as they’d been left when the last soldiers disembarked.

When he found out the ship was scheduled to be scrapped, Beltrone said he and his wife asked the military if they could recover the canvases and other items to preserve the memory of the soldiers who traveled on the ship. The ship was taken apart in Texas in 2005, but Beltrone had recovered the graffiti from inside the ships.

“We did not want to see that material lost and those men forgotten,” Beltrone said. “It’s not just an artifact. It’s someone talking back to us through time.”

Then the work began on telling those stories. Many of them signed their work and left messages about their hometowns or loved ones, which made looking them up easier. Beltrone said he still gets emotional when they read the little notes drawn on the canvas about insecurities and homesickness — only to find that the person who wrote them was ultimately killed in Vietnam.

“We found roughly 100 people who did the graffiti,” Beltrone said. “Sometimes they don’t remember at first. I’ll ask them, ‘are you a Vietnam vet?’ and they’ll say ‘Yes.’ I’ll ask ‘How did you get there? Do you remember the ship name?'”

Once he’s confirmed that the person is the veteran in question, Beltrone’s found a humorous way of breaking the ice.

“You defaced government property in 1967 and Uncle Sam would like $87 in reimbursement for damages,” Beltrone would say.

Beltrone shared the stories of dozens of soldiers, sometimes playing audio clips from interviews where soldiers talked about humorous or bizarre incidents from the voyage — like the information shared by soldiers at a stop-over in Okinawa being exploited by Vietnamese propagandist Hanoi Hannah in messages aimed directly at them. Joe Bell, one of the veterans Beltrone interviewed, said it was unsettling to be heading into a warzone where they knew nothing about the enemy and hearing radio messages describing intimate details of their lives.

At the CNA event yesterday, employees said the exhibit helped put a face on the kinds of military quality-of-life issues the organization deals with. Staffers at the non-profit told the audience that a replica of the graffiti will remain at CNA.

“We deal with recruiting and retention as well as quality of life, and CNA prides itself on a deep understanding of the problems we deal with,” said Linda Cavalluzzo, director of Resources and Force Readiness Division for CNA. “This makes it personal. It comes alive and it’s not just numbers on the page.”

“I got a comment earlier that men now come back [from war] in hours,” Beltrone said. “How do you decompress from that? Many came back from Vietnam on planes, but some came back on ships. They left messages for those who would be on after them saying things like ‘I made it back and so can you.'”

Armstrong ultimately made it home to his wife in South Carolina and raised a family.

Beltrone said that when he asks soldiers why they wrote on the canvases, even though it broke regulation, there’s one response he gets more than any other:

“What were they going to do, send me to Vietnam?”