Health Matters is a biweekly opinion column. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

Health Matters is a biweekly opinion column. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

Holiday season is fast approaching, and millions of people are weighing the risks of air travel versus staying home. The decision is intensified by the fact that many have not seen family for almost a year, and driving long distance just isn’t an option.

While the thought of being confined in a small space with strangers for hours is daunting, recent studies have suggested that flying may not be as dangerous for COVID-19 spread as once thought, and that cabin air may in fact be cleaner than air in hospitals.

This idea that flying may be safer than the hospital or supermarket is an idea airline companies are extolling and fervently proclaiming to all willing to listen. The airline industry has been among the hardest hit by COVID, with travel dramatically declined compared to 2019.

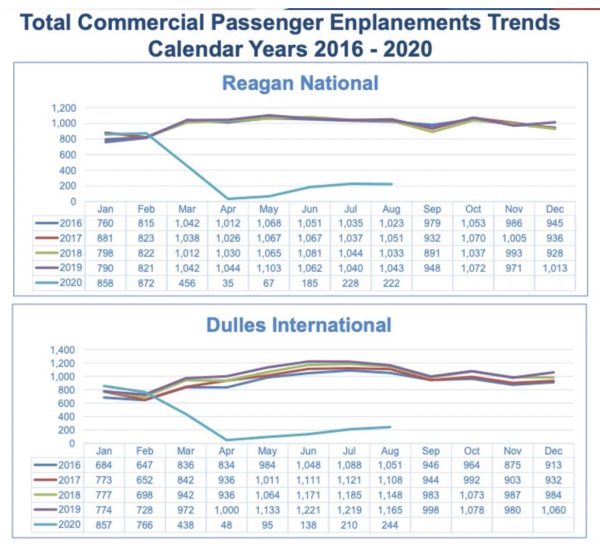

For Reagan National and Dulles International, domestic commercial passenger activity was down nearly 80% this August compared to August 2019. The airliners message of safety seems to be resonating, as the most recent data from Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority shows that the number of domestic passengers has more than tripled at Reagan and more than doubled at Dulles, after bottoming out in April.

The airlines have put in substantial effort to research airplane safety, and perhaps the most convincing study sponsored by United Airlines was just released, albeit not peer-reviewed. Using human-like mannequins and high-tech particle counters in proximity to simulated sick passengers, researchers concluded that the risk of aerosol viral dispersion is reduced 99.7% due to high air exchange rates, HEPA-filtered recirculation and downward ventilation.

High air exchange rates means the entire volume of cabin air is replaced every three minutes, with 75% coming from outside the plane and 25% recirculated after going through HEPA filters. While ventilation system is running, air travels from the ceiling to the floor, reducing risk of horizontal transmission. In other words, risk of transmission is highest if the infected passenger is in the same row, and much lower in the rows ahead and behind.

All the mannequins and nanometrics in the world can tell us flying is safe, but are people actually getting sick? Recent studies from the International Air Transport Association purport 44 COVID cases associated with air travel out of 1.2 billion passengers traveled since the start of 2020.

The low numbers corroborate with the results published by the Journal of Travel Medicine last month, which looked at all peer-reviewed publications of flights with possible transmission. They concluded that “the absence of large numbers of confirmed and published in-flight transmissions of SARS-CoV-2 is encouraging but is not definitive evidence that fliers are safe.” On October 27, a study from Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health reinforced that with masks and proper cabin ventilation, there is a “very low risk of SARS-COV-2 disease transmission on aircraft”.

Despite these positive studies for airline safety, not all have been glowing. One study looked at two passengers and two attendants flying 15 hours from Boston to Hong Kong testing days later with the same strain of COVID, suggesting virus transmission during air travel.

Another study looked at a flight from London to Hanoi, where 16 passengers, many in business class, were found to have COVID, suggesting proximity as a major transmission factor. Both studies were in the journal Emerging Infectious Disease and both were in March before masks were mandatory. More recently, a report was published that despite precautions and low flight numbers, more than 100 air marshals have become infected since COVID began.

My take after compiling all the data is that air travel is risky, but less than I first thought. Masks, high air turnover, HEPA filters, downward ventilation, staggered boarding and disinfecting between flights are the most effective safeguards already in place. Yes, most of these big studies are funded by the airline industry and thus susceptible to bias, but the retrospective studies reporting sick passengers are not funded by airlines.

Being on the airplane may actually be safer than all the events leading to boarding such as check-in lines, bathrooms, security screening, taxi, train, etc. I agree with the CDC that staying home is safest, but I also am pragmatic enough to know people will fly. If you decide to fly and are asymptomatic with no recent COVID exposure, there are things you can do to make air travel safer:

- Book flights at unpopular times — less people onboard means less exposure.

- Follow social distancing at all times from check-in to boarding.

- If flying alone, choose the window seat. There is less proximity to people moving in the aisle, getting luggage overhead and going to the lavatory. There is also less number of people surrounding since window acts as a physical barrier.

- Wipe high traffic surfaces with disinfectant before seating. Most airlines disinfect between flights, but it doesn’t hurt to double up.

- Turn on the overhead air vent while everyone boards. Not all airlines have ventilation on while boarding, and this is one measure you can control.

- Limit eating and drinking if possible, decreasing time without a mask.

- Monitor the latest COVID data at the destination. If there is a major spike occurring, it may be best to delay travel to a hotspot.

This is by no means an exhaustive list of studies, many more are out there and coming out on a weekly basis, but I think these are the more salient examples.

What do you think? Do you feel safe to fly? If not, when would you feel comfortable flying? Do you have any other safety tips for flying?

Dr. George C. Hwang, known to his patients as Dr. Chaucer, is a practicing anesthesiologist who also helps to run Mind Peace Clinics in Arlington. He has written for multiple journals, textbooks and medical news outlets, and has been living in Arlington for the past 15 years.