Lyon’s Legacy is a limited-run opinion column on the history of housing in Arlington. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

“Discrimination! Why that is exactly what we propose… That exactly is what this convention was elected for — to discriminate to the very extremity of permissible action under the limitation of the federal Constitution, with the view to the elimination of every Negro voter who can be gotten rid of.”

Carter Glass, Virginia Constitutional Convention, 1902

Arlington wasn’t always white. Before 1900, the population of the county was nearly 40% African-American. By 1950, it was less than 5%. Today, the number is still less than 10%.

This is the third part of Lyon’s Legacy, a biweekly series on ARLnow (you can read the whole thing, with citations, here). It will tell an eight-part history of how Black people, and other groups that experience racial or economic discrimination, have been excluded from living in Arlington County. Last week, the story told who Frank Lyon was and what he found when he arrived in the county. This week, it will tell how he began to leave his mark.

In 1901, Frank Lyon and Crandal Mackey travelled to Norfolk to attend the Virginia Commonwealth Constitutional Convention. As at similar conventions across the South, the convention’s leaders hoped to use the resurgent power of white Democrats to upend the Reconstruction-era constitution that had enfranchised Black citizens.

Lyon served as Clerk of the Committee; Mackey was one of our county’s delegates. In Norfolk, they heard Senator Carter Glass say that the “white race” held the “divine imprimatur of that intellectual and racial supremacy which gave them the exclusive right of government.” Glass’s new constitution was about to give Lyon and Mackey just the advantage they needed to reshape our county in the convention’s vision of “racial supremacy.”

The 1902 Virginia constitution was imposed without popular approval and it systematically disenfranchised African Americans across Virginia. A poll tax was levied. Land ownership was made a condition for voting. The statewide electorate was cut in half. Jim Crow reigned. The new constitution remained in place until 1971.

Across the nation, the Progressive movement brought reforms at the turn of the century. It fought political corruption, regulated labor standards, and modernized the schools. But: “The blind spot in the Southern progressive record — as, for that matter, in the national movement — was the Negro, for the whole movement in the South coincided paradoxically with the crest in the rise of racism. The typical progressive reformer rode to power in the South on a disenfranchising or white supremacy movement.”

Crandal Mackey, and the rest of the Good Citizens’ League, was no exception.

A year after the constitutional convention, Mackey ran for Commonwealth’s Attorney. The incumbent, Richard Johnston, was a white landowner whose family sold a neighborhood’s worth of land to the county’s Black residents. Mackey took on Johnston in an election with heavy racial overtones.

“The reduction of the negro vote… under the new Virginia constitution, helped Mackey wonderfully,” wrote the Washington Times. He won by two votes.

Frank Lyon didn’t run for office. He bought the county’s preeminent weekly newspaper, the Alexandria County Monitor. As the historian Lindsey Bestebreurtje describes, “under Lyon’s leadership as owner and editor, The Monitor pushed League policies and opinions.” He built an image of Alexandria County as a desirable suburban retreat for Washington’s growing upper-middle class. He also built an image of Black people and saloons as obstacles to progress.

Lyon and Mackey began to shape the physical landscape of the county. They wanted to prime the land for development. For that, they needed infrastructure to support the twentieth-century comforts that would-be-suburbanites demanded: paved roads, sewer lines, municipal water, expansion of gas and electric lines. Wielding their influence in government through the Good Citizens’ League, Lyon and Mackey got the county to build this new infrastructure — and they made sure that it would only benefit white neighborhoods.

The year was 1904. Lyon’s gang had hit its stride. They were in office, they owned the paper. They were ready to build houses and make their fortunes. But Rosslyn still stood between Washington’s middle class and their suburbs-to-be: Rosslyn, its saloons, and its Black population.

Lyon’s power with the pen wasn’t enough. The rebel’s son also held a gun.

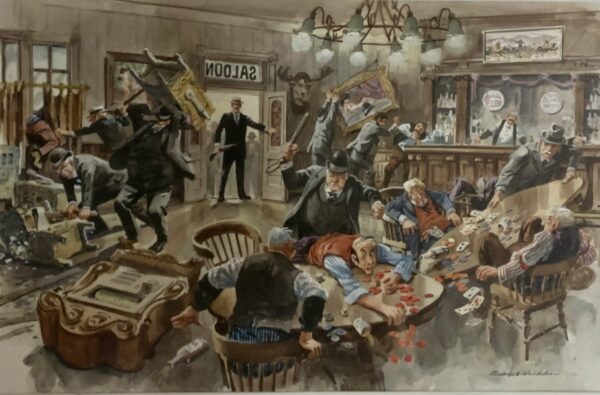

May 30th, 1904. Daylight. A streetcar grinding along the rails of a bridge from Washington. Inside, Crandal Mackey — Commonwealth’s Attorney — opened a sack bulging with weapons.

Mackey handed these weapons to his posse of deputized volunteers: axes, sledgehammers, shotguns. Frank Lyon took one. Their gang of six arrived in Rosslyn, stepped off the streetcar, marched through the dusty streets toward the riverside, and arrived at a saloon called Heath’s Place.

They battered the door down. The place was practically empty — only a few gamblers sat around the tables. Mackey’s posse bashed in the slot machines, hacked up the bar, shattered the jugs of whiskey, handcuffed Eddie Heath, and carted him and two of his employees to jail. Then they stormed on to the next saloon.

In that day of destruction, the posse fired only a single shot. They aimed at the back of a fleeing, unarmed man.

The man was convicted of no crime, running from the gun, lucky that the round missed. He was Black. Mackey’s shotgun hangs today on a ceremonial plaque in the Arlington County sheriff’s office, memorializing the day of vigilante violence that cleared the way for white suburbs.

D. Taylor Reich is a native of Arlington and a graduate of H-B Woodlawn. They work as a researcher in urban mobility analytics with the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, where their research has been covered by international publications including The Guardian, BBC, and China Daily. Previously, they were a Fulbright scholar in Amman, Jordan. Taylor has served on the Arlington Transportation Commission and the Plan Lee Highway Community Forum.