There has been a mini-spate of deaths and reported suicide attempts among Arlington Public Schools students in the last month, ARLnow has learned.

A middle schooler died after Christmas and a high schooler died in mid-January, according to sources in the school community.

Medics have been dispatched to Arlington schools a number of times since the end of winter break, for suicide attempts, overdoses and other substance abuse issues among students, according to scanner traffic. In one instance, medics were dispatched twice in one day to the same school for reports of suicide attempts through taking pills.

“Based on anecdotal information — reports from principals and Student Services personnel — we do remain concerned about the needs of our students and how they are handling the multiple impacts to their lives and how those are manifesting themselves in some of their choices, behaviors and statements around mental health,” Darrell Sampson, APS Executive Director of Student Services, tells ARLnow.

He couldn’t comment on specific cases, citing privacy concerns.

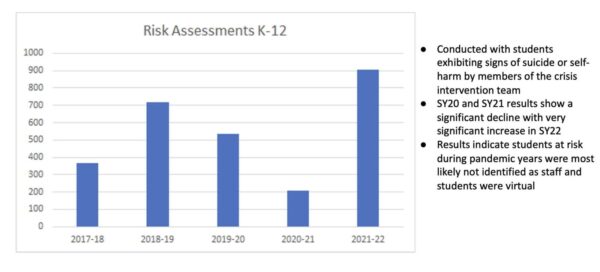

These incidents are part of a broader trend upward in mental health needs among children. Sampson says during the 2021-22 school year, APS saw a “significantly higher” number of suicide risk assessments compared with the 2020-21 academic year. Meanwhile, clinicians with Arlington County Dept. of Human Services reported seeing more students exhibiting self-harming behaviors.

Generally, he said, school mental health professionals are seeing students struggling to navigate stressful life experiences because they have fewer past social interactions to draw from due to pandemic-era isolation. APS ended in-person learning in the spring of 2020 and resumed in-person instruction for all students midway through the 2021-22 school year.

“You have kids… who have missed out on years of being able to build those resiliency skills and social-emotional competencies through everyday experiences,” he said. “Now, they’re back in school and they’re experiencing the same things our students have always experienced in school — whether that’s struggles with a class, or with friends, or struggles with everyday experiences — and their bag of skills is just not at all [equipped] and when things happen in our lives that are stressful it can impact them in more intense ways.”

Elizabeth Hughes, the senior director for research at the Community Foundation for Northern Virginia, tells ARLnow mental health is worsening among children in the entire Northern Virginia region. She will be releasing detailed findings next Wednesday.

Some 37% of public high school students experienced recent symptoms of clinical anxiety and depression last winter and 34% reported past-year persistent sadness, according to her forthcoming report.

One in 10 high schoolers seriously contemplated suicide over the past year, with comparably high rates among middle school students. Just under one in two high school students in the region had past or recent mental health needs.

She says the pandemic only accelerated a longer upward trend in anxiety, persistent worry, sadness and loss of interest among teens.

“The [American Academy of Pediatrics] has declared a national emergency around children’s mental health, but the word ’emergency’ feels so much more ephemeral than what we are seeing,” she said. “More youth than ever need help, yes. But this story is so much bigger than the aftershocks of a pandemic.”

Signs of worsening mental health

A patchwork of local, regional and statewide data indicate that more children are experiencing feelings of anxiety and depression, or are contemplating suicide.

First, APS conducted some 900 suicide risk assessments in the 2021-22 school year, up from more than 700 in the 2018-19 school year. Decreases in the 2019-20 and 2020-21 school years were attributed to children not being identified due to virtual learning.

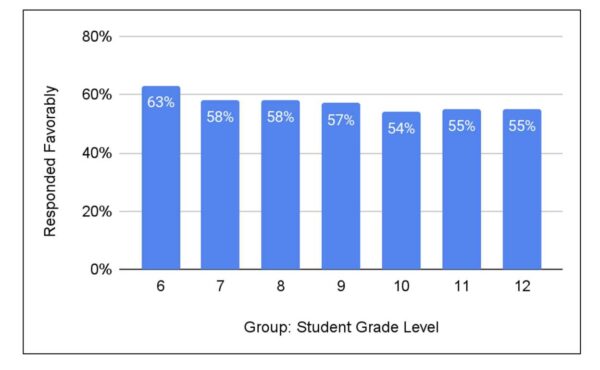

A 2022 survey of APS students found that students are most likely to report having positive feelings about themselves in sixth grade, but that sentiment tapers as they progress through middle and high school.

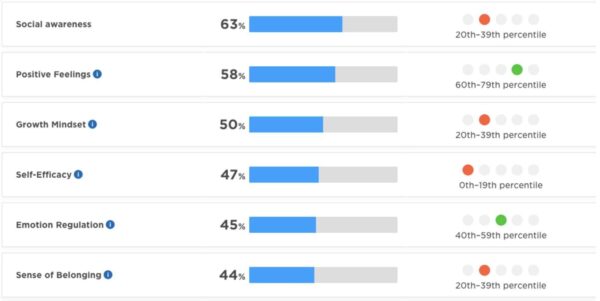

Meanwhile, less than half of middle and high schoolers reported having a sense of belonging or feeling able to regulate their emotions or set and achieve goals.

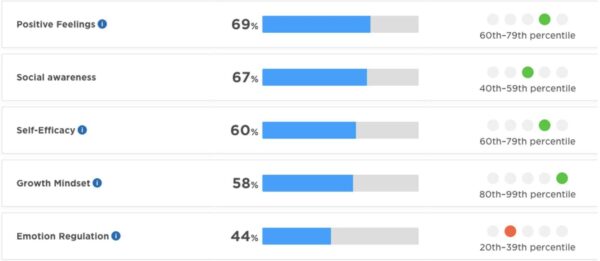

Those rates were higher for students in grades 3-5.

In the second half of 2021, Arlington County Dept. of Human Services says it saw “a significant increase in the number of clients receiving intakes and being admitted to services with the highest clinical need which included children exhibiting self-harming behaviors, suicidal ideations and attempts, psychiatric hospitalizations with decreased hospital beds for youth,” per a department performance report shared with ARLnow.

Despite the increase in need for mental health services, DHS has been serving fewer clients, largely attributed to an increase in staff vacancies and a corresponding decrease in operational capacity, per the DHS performance report.

Children are experiencing more “life stressors” and have fewer “protective factors” to cope, Hughes says. Reviewing a Fairfax County survey of students, she said 28% of high school students have fewer than two protective factors, including positive relationships with adults, involvement in activities and the community, and self-esteem, compared to 21% pre-pandemic.

“I was surprised to see how much of a difference having a caring adult in the community made in these rates,” she said. “Sadly, many, many youth do not have this resource, and it seems like an obvious area on which the community can focus — mentoring, coaching, and finding other ways to form a bond with a teen outside your family.”

Hughes said targeting adult mental health needs would help improve how children feel about themselves. Some 26% of adults have mental health needs, particularly those most present in a teen’s life: people of parenting age, working in the schools and in healthcare.

“If we want to expand the number of trusted, caring adults who can support our youth in crisis, we also need to support our adults in crisis,” she said. “Not just mental health services, but programs and services that address some of the root causes of these issues, like material insecurity, isolation, and need for community and purpose.”

She recommended community members and caregivers prioritize sleep, reduced screen time and moderate homework for children.

“Obviously, these buckets of activity — time engaged in school and activities, time sleeping, time on a screen, and time for everything else — must all fit into a 24 hour day, so youth who over-invest in one activity are likely depleting another,” she said.

What APS is doing

Any time a student or staff member dies, Sampson says Student Services will partner with a school to provide services such as small group discussions with an individual’s friends or a classroom discussion.

“If there are a number of losses in a short period of time, regardless of the means, we do want to make sure we are looking at district-wide supports, messaging, opportunities or curriculum or trainings to make sure we are giving the communities, the students and the staff the skills they need to follow up and support that particular community,” he said.

At the start of this month, APS sent out two emails, one drawing attention to its efforts to prevent drug overdoses — a few months after ARLnow reported concerns from parents about drug use — and another reminding the community how to respond when someone is struggling. That mental health messaging was reiterated after an elementary school shooting in Newport News.

Meanwhile, APS is working on a system-wide roll-out of a standardized curriculum that teaches kids basics about how to regulate and manage their feelings, as well as skills for connecting with peers and understanding themselves, known as social-emotional learning.

“We’re continuing to build that out as a district so our students are getting those basic skills to be successful in school and post-secondary and in life,” Sampson said.

Middle and high school students learn about how to spot the signs of suicide risk in themselves or in their friends and are taught which adults to talk to in those situations, he said.

“Students can be highly supportive of each other and students will come forward and share that they are concerned about a friend,” he said. “We consistently emphasize the need for the students to know when is a time to bring an adult in.”

Struggling to hire more mental health professionals

This month, parents who sit on the APS Student Services Advisory Committee sounded the alarm on these needs and urged the school system to increase funding for full-time social workers and psychologists.

“There is not sufficient mental health care available to our children locally to meet the needs that already exist and are expected to continue,” the committee said in a Jan. 4 report. “This makes it more important than ever that APS have adequate internal resources to address rising needs for students.”

“Not all elementary schools currently have full time services for their students, and some school psychologists and social workers have multiple school responsibilities,” the report continued. “Student needs for school psychologists and social workers do not match the availability of these professionals.”

Even though funding additional full-time social workers and psychologists could cost some $2.2 million per year, per the report, the committee said “this need is too great to be left unmet.”

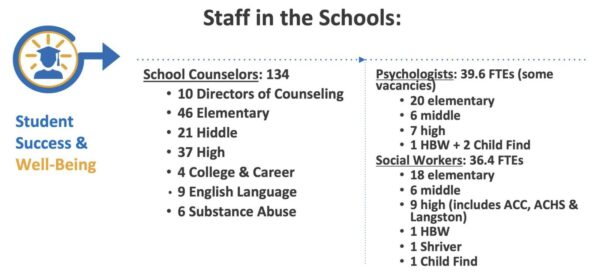

APS has counselors at every school and psychologists and social workers assigned to each school, as well as division-wide substance use counselors, Sampson said. Still, he says, it can be hard to fill vacant positions, let alone create new positions, amid a shortage of available mental health providers.

As of today (Thursday), there was a middle school counselor position vacant since August 2022, in addition to an elementary counselor position posted yesterday.

Proposed state legislation to develop a template memorandum of understanding between school systems and governments for the exchange of mental health services could help, Sampson said.

“There’s a challenge with providers in the community and that’s put pressure on schools because, if people are on six-month waiting list for a community provider or a private provider for a particular intervention or support, that puts more onus on us and the schools to support student mental health,” he said. “We are doing a lot of leg work to try and support the mental health and well being of our students because the community is also struggling to find providers and meet the need — not just of children and adolescents but also the adult population.”