Granny flat, in-law suite or accessory dwelling unit: Slowly but surely, these standalone homes, known by many names, are starting to be built in backyards in Arlington County.

“These are not tiny homes,” said Michael Novotny, the owner of Backyard Homes, which builds accessory dwelling units, or ADUs. “These are real, high-functioning, high-performing homes that you can move into and you can live very comfortably in.”

ADUs, which can take the form of a basement or attic apartment or standalone structure, are built on existing properties but are separate from the primary residence. They have been billed as a low-cost way to boost affordable housing stock.

The County Board first approved standards for these buildings in 2008, and last amended those standards in May 2019 to encourage more construction. From when the changes took effect in July 2019 until January of this year, the county says it has approved applications for 57 accessory dwelling units.

As of 2019, Arlingtonians living on land zoned for single-family homes can build detached ADUs on their property without first seeking county permission. Previously, homeowners could only build such a unit inside their house or convert an existing outside structure into one.

New ADUs have to be at least 5 feet away from the property lines, and on corner lots, 5 feet from the side yard line and 10 feet from the rear yard line. To be used as Airbnb or VRBO units, owners must apply for an accessory homestay permit.

Of the 57 applications approved since July 2019, 22 were for new detached dwellings, 24 were for attached dwellings and 11 were converted from existing buildings, said Jessica Margarit, a spokeswoman for the Department of Community Planning, Housing and Development.

She cautioned that ADUs alone cannot solve Arlington’s lack of housing options.

“Accessory Dwellings can add to the variety of housing options that are available in Arlington, but are not intended as a stand-alone solution to Arlington’s housing shortage,” she said. “The county is exploring a range of ideas to address housing supply and housing affordability through the Housing Arlington initiative.”

Local developers and housing experts say that 57 units since 2019 is a small number compared to where ADUs are flourishing: in Los Angeles County and Humboldt County in California, and the cities of Seattle and Portland. They attribute Arlington’s current pace to barriers in county policies and financing hurdles.

“The biggest current barrier in Arlington is that the county has an owner-occupancy requirement in place,” said Emily Hamilton, a Senior Research Fellow and Director of the Urbanity Project at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. “It creates barriers to homeowners who want to add one.”

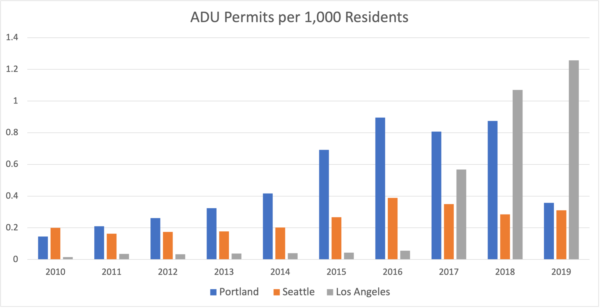

Arlington requires owners to live in either the “big house” or the ADU on the property. Hamilton said in Portland, Seattle and Los Angeles — where there are no owner-occupancy requirements — ADUs are proliferating, citing the number of permits per 1,000 residents, shown below.

The owner-occupancy requirement has two effects on financing backyard cottages, she said.

First, homeowners face difficulties getting loans because banks do not view these dwellings as good collateral, she said. If a homeowner defaults and the bank takes over the property, it could not lease the two units separately, which is bad news for the bank.

Second, building an ADU does not make financial sense in a place with owner-occupancy laws, as the appraised value of a home does not increase to reflect an ADU’s potential rental income, she said. In California, where owner-occupancy laws are banned, ADUs can increase a valuation by 20-40%, she added.

“If you want to see large numbers of ADUs getting built and being rented to long-term tenants, you need it to make financial sense for the homeowner,” Hamilton said.

Most people who build ADUs want to rent them out to other people looking for a primary residence, she said, citing a study where 51% of respondents rent them out, 9% use it as extra space for main-house residents and 12% use them for short-term rentals.

But in a report from 2017, county staff defended owner-occupancy requirements because they keep people from purchasing homes with the goal of developing the property into “a defacto two-family property” for investment income.

Not requiring owners to occupy the main house, the report continued, would be at cross-purposes with the goals of the changes: “enabling homeowners to receive additional income from the rental unit enabling them to more easily afford their home and/or helping older adults age in place.”

That tracks with what Novotny said he sees among his clients.

“I find more people are interested in these for their parents to move into or returning college students or visiting family members,” he said. “Our clients want ADUs to be a nice part of the fabric of the lot.”

Novotny, who founded his company last year, said he designs ADUs that “feel like nice condominiums.” He said in his experience, many homeowners do not know about this expansion option, or think they are too small to live comfortably in.

Units from Backyard Homes typically range from 560 to 750 square feet, although one model clocks in at 460 feet, and cost between $170,000 and $225,000, he said. With high ceilings and lots of windows, they feel lighter and bigger than similar-sized apartments, he added.

“A lot of people do additions but this can be an even better strategy,” he said.

Chart courtesy Emily Hamilton