(Updated at 8:40 a.m.) Bad news: the Marceytown treasure is probably a myth.

It’s one of those little local history stories that, according to local historian Kathryn Springston, starts from one fact but gets distorted by years of retelling. The good news, Springston says, is that behind many of the exaggerated local legends are equally fascinating but underreported true stories.

Springston is planning to discuss some of hidden legends of Arlington’s history in an upcoming four-weekend lecture series covering Arlington’s pre-colonial history up through the beginning of the 21st century.

The program is part of the Smithsonian Associates Streaming series and will run every Saturday in February from Feb. 6 to Feb. 27. from 9-11 a.m. The program is $100 for members and $110 for non-members.

Springston has been hosting walking tours in Arlington for 40 years, but said she had always wanted to do a longer, online lecture series.

“I used to do walking tours, which were terrific, but they’re always so short,” Springston said. “I wanted to give people more… When we switched to virtual programs and doing this all online I kept thinking: maybe this would be a good time.”

The chance came when Springston broke her foot last year and she was asked to appear as a guest speaker on tours.

“What we came up with is an abbreviated, short course,” Springston said, “but if it works, I want to make it longer and more in-depth. Even with eight hours, my husband always said I could go nonstop about Arlington history.”

The last class will cover the arrival of the Metro and government contracting jobs in the region, as well as the struggle to desegregate Arlington. It’s an area Springston said is rife with unsung hometown heroes, like Dr. Oscar LeBeau, a local who Springston said fought passionately against segregation for years.

It’s a story Springston says is important to tell, particularly in contrast to efforts to lionize some local figures like Frank Lyon, for whom Lyon Park is named.

“People raise up Frank Lyon as a hero, but if you look at deeds it said no one who was not Caucasian could live or work on his properties,” Springston said.

As for Marceytown, Springston said the concept of the town didn’t exist until around 1900 and that it wasn’t where many say it was. The primary source of the treasure story is Eleanor Lee Templeman’s 1959 book Arlington Heritage, but Springston said much of Templeman’s stories came from State Sen. Frank Ball.

“Wonderful woman, told wonderful stories, but when I ask her where she found a fact it was always ‘Senator Frank Ball told me,'” Springston said. “Frank was a long term resident, but your mind gets fuzzy as you get older and you might not remember things. Sometimes people misremember or embellish thing. So when she would tell me that, I would discount these stories until I verified.”

There’s the good news through: Springston has another lost Civil War treasure story. According to her:

The story about the treasure is a great story, there was however one actual Civil War instance of treasure that people have never found. [The Union] lost a wagon-load full of payroll money because, according to the story, the paymaster… was headed down Military Road when he heard shots behind him. This was just after Battle of Halls Hill so the paymaster… whipped up his mules and when the wagon got away it crashed into a creek. He took off running and got to Military Road where the Cherrydale Baptist Church is and found a couple men who were patrols from Fort C.F. Smith. They galloped back and the wagon and mules were all gone.

“Somewhere,” Springston said, “that money disappeared.”

Springston said that story has been twisted around and interpreted in several ways, one of which ties in with another eccentric local figure: Luke Carter.

Carter, Springston said, was a free Black man living with his wife above Chain Bridge in a free Black community. Carter was a farmer who frequently testified and supported his neighbors at the Southern Claims Commission.

“In one, it’s noted that he came in with a gold-headed cane,” Springston said. “He was asked where he got it and he said a friend gave it to him. One of the stories went around was that Luke Carter took [the treasure] but that can’t be proved. The Carter family has descendants out near Ruckersville but they say he wouldn’t have done that. It’s another great story that’s gotten twisted over time.”

Springston says she hopes her lecture series will help separate the fascinating and true local history from the mythology.

“That’s one of the reasons I wanted to do this program,” Springston said. “There’s so much out there. I’m not going to spend hours debunking stories, but I want to tell people there’s a lot more to Arlington than the stories.”

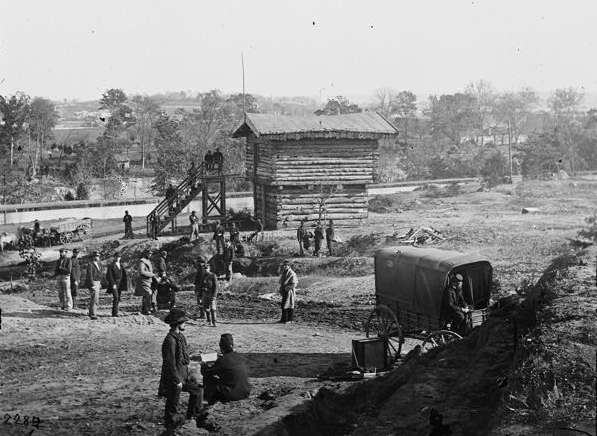

Image via Library of Congress