This reporting was supported by the ARLnow Press Club. Join today to support in-depth local journalism — and get an exclusive morning preview of each day’s planned coverage.

Last year, an attempt to broaden the Arlington police auditor’s access to police records quietly fizzled before reaching the public for discussion.

The auditor currently can access police records for publicly filed misconduct complaints and review summaries of the Arlington County Police Department’s internal investigations, which ACPD has about a month and a half to generate and anonymize.

The fizzling ensures that, for the near term, the auditor continues to have fewer powers than the state code allows, than what auditors in Alexandria and Fairfax County enjoy, and than what the National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement says is essential to effective oversight.

In June, then-County Board Chair Christian Dorsey and member Matt de Ferranti introduced draft changes that would have granted auditor Mummi Ibrahim full access to all ACPD records deemed necessary to do her job, including complaints against officers going back five years, and “unrestricted and unfettered access” to software storing those records.

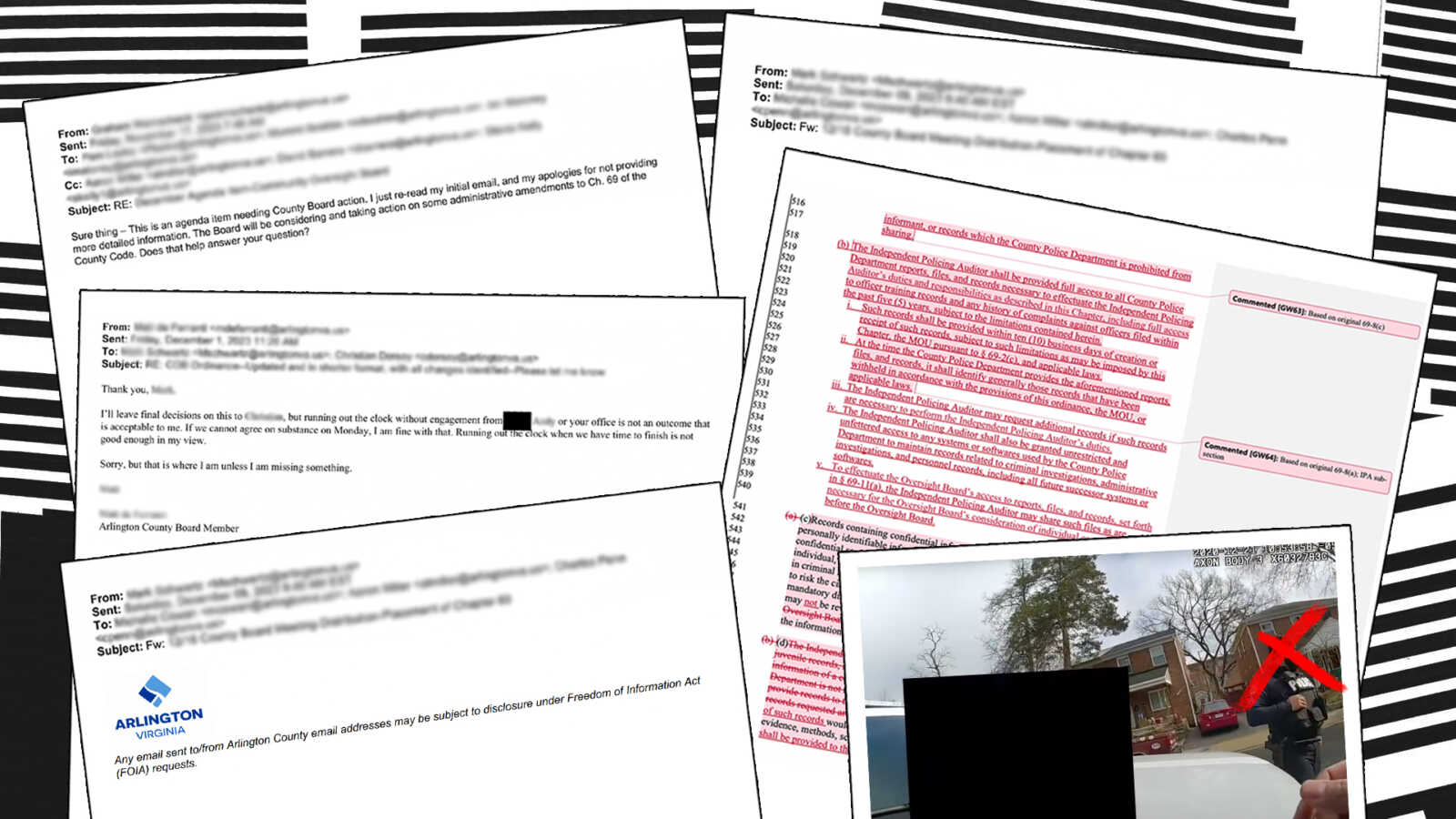

By December, with Dorsey leaving, time was running out for a Board vote. Before the Board met on Saturday, Dec. 16, 2023, Board members, county officials, ACPD leadership and the Independent Policing Auditor (IPA) exchanged a flurry of emails about the nature of the changes and whether to approve them. ARLnow reviewed these emails, which were obtained via a Freedom of Information Act request and shared with us.

Ultimately, the revision attempt fizzled for multiple reasons, according to interviews and emails in the 444-page FOIA. Not all Board members deemed the broader powers necessary, and there were concerns the changes would reopen the county’s collective bargaining agreement with the police union. The county did not have support from ACPD leadership, while Dorsey and interim member Tannia Talento were leaving their posts in two weeks.

After the murder of George Floyd in 2020, a swath of Arlington residents agitated for police accountability in their community. A Police Practices Work Group recommended some 100 reforms, including creating a Community Oversight Board (COB) and an office of the policing auditor to review police misconduct complaints.

Establishing an independent auditor, however, got off to an inauspicious start in Arlington after Gov. Glenn Youngkin in March 2022 blocked a local charter bill that would have given the Board the same power to hire an auditor that other Virginia boards have. This dismayed elected officials, who said the auditor has less independence if she reports to Arlington County’s chief executive, County Manager Mark Schwartz.

The events of last year reveal county leadership is divided when it comes to implementing these reforms. When asked about that split, Arlington County Board Chair Libby Garvey said Board members “generally support the powers and access that the IPA currently has under our ordinance.”

“We know that effective civilian oversight is not one size fits all and we anticipate continuing to learn and refine our approach to best meet Arlington County’s needs over time,” she said.

“We are confident that the auditor and COB are enabled and capable of conducting and completing independent investigations with the information available to them,” she continued. “If the Auditor or the COB deems additional types of information to be necessary for them to fulfill their duties under the ordinance, the recourse of a direct request to the County Board for an ordinance change is available to them.”

The COB and Ibrahim, meanwhile, contend that it is harder to do their jobs without greater records access.

The aggregated summaries of internal investigations ACPD provides “do not facilitate the full transparency needed for effective civilian oversight,” COB Chair Julie Evans said in a statement to ARLnow. “Access to internal investigations will allow the IPA and COB to monitor for and help ACPD to address any systematic issues that may arise. These issues, if unaddressed, could otherwise jeopardize both public and officer safety as well as community trust in law enforcement.”

Ibrahim said something similar about a fully empowered civilian oversight entity in a recent panel organized by the National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement.

“It can help predict risks in the future,” she said. “It can help to ensure a safer environment for your police officers to go into the community and for community members to experience policing, and a better outcome overall. If you’re not looking at civilian oversight as an asset, you are certainly missing the point of what we’re trying to do here.”

With only access to summaries of internal investigations and redacted body camera footage, Ibrahim could not, for instance, verify the summaries sent to her or see if the involved police officer has a disciplinary history.

Meanwhile, Alexandria’s police auditor has full access to unredacted police records related to investigations into complaints filed either with their oversight board or the police and she can can review completed internal investigations.

Nor does Ibrahim have the ability to make her reviews publicly accessible. Hers go to the Community Oversight Board and ACPD, while Fairfax’s auditor publishes his reviews online.

She attributes these variances, in part, to the fact that jurisdictions like Arlington stood up their oversight “proactively… without some sort of precipitous event or being under a consent decree” that mandated certain powers.

Dorsey and de Ferranti’s revised ordinances were developed one year after Ibrahim was hired. By Dec. 1, however, de Ferranti appeared frustrated with the pace of the internal review of the revisions.

“Running out the clock without engagement from… [Police Chief] Andy [Penn] or your office is not an outcome that is acceptable to me,” he said in a Dec. 1 email to the county manager. “Running out the clock when we have time to finish is not good enough in my view.”

As the Dec. 16 meeting drew near, a draft ordinance describing generally “administrative” changes guaranteed a level of access comparable to what county code and a Memorandum of Understanding already enumerate.

The Board was set to vote on the ordinance that Saturday but the Arlington branch of the NAACP intervened, asking the Board to delay its vote until a public discussion could be had the following Tuesday.

“Not a single member of the public had any opportunity to engage or provide any input on the 170+ changes that were made last year,” NAACP President Mike Hemminger told ARLnow in a statement.

“The process the Arlington County Board took last year perpetuates a long history of insularity in our county governance,” he continued. “It reveals an alarming power inversion in which the police seem to lead elected officials instead of elected officials leading law enforcement by engaging with the community. The trajectory of this outcome is woefully misaligned with this political moment in history.

Instead of pushing it to Tuesday, De Ferranti and Dorsey consulted fellow members and the Board modified its own motion, voting Saturday to defer the changes indefinitely. They expressed their regret in emails confirming the deferral.

“The revisions are modest and some of them, despite all our efforts, are not as thought through as I would like them,” de Ferranti said in a Dec. 15, 2023 email. “I want to thank you for all the work put into this. I am sorry we weren’t able to get to more agreement, but believe this is the best decision in this case.”

Dorsey said he appreciated all of the engagement and consideration that went into the proposed ordinance changes.

“I apologize to each and all of you that such an effort was not rewarded by an outcome that could demonstrate the progress that was made,” he said. “As time is among our most important resources, I want you to know that I am deeply sorry to have wasted yours, and am chagrined that I won’t have an opportunity to try and make it up to you.”

It is unclear the level of influence the police department had on the outcome. ACPD did not comment for this story and the county redacted emails that appear to include memos from the department, detailing their input on the June changes or discussing records access.

Unredacted emails and interviews suggest two areas of concern. First, Chief Penn and Schwartz questioned the need to revise the ordinance before the oversight board and auditor completed more investigations. Second, the changes could “reopen” the collective bargaining agreement with the Arlington Coalition of Police, the local police union.

In July, Penn sent an email saying the proposed changes from June were not “generally administrative in nature.” He also disagreed with the Board for saying it sought the changes because there have been “challenges in the implementation” of the current ordinance, given that “the processes have not been fully exercised yet.”

In November, Schwartz made a similar point.

“As much as it is important to get the ordinance in good shape, I am very anxious over the pace of the process… [T]he ability to point to a process that gives complainants an answer to their complaints in a timely fashion is open to debate,” he said. “Some of this is directly related to staffing needs.”

Evans, the COB Chair, said last week that the auditor has completed 77 investigations so far but not all of them required COB review or a public hearing.

The COB completed its first investigation in October and has held public hearings on five investigations, will cover two more this Wednesday, and is working to clear six outstanding investigations and to address the 21% increase in public complaints submitted between April and December of last year.

“The COB, IPA, and ACPD are also working together to refine our 2024 complaint priorities, taking into account what we’ve learned in the first six months of conducting investigation reviews to improve complaint processing, response, and reporting times,” Evans said.

Meanwhile, Penn signaled to the county in December that his department “disagreed with and would not support” the changes in an email he shared with the Deputy County Manager, intended for rank-and-file officers.

“There will be many further conversations about this in the coming week(s), and we remain very optimistic this will work itself out,” he said, adding that he would be working with union leadership on this issue in the coming days and weeks.

For the union’s part, ACOP President Randall Mason tells ARLnow the organization was aware of these conversations but did not play an active role in them.

“We never had any conversations with the County Board members as they worked their way through that process,” he said.

He says ACOP did not have issues with the proposed revisions that were published in mid-December. When asked if greater access to police records could trigger revisiting ACOP’s agreement, or CBA, he said “any changes to working conditions of ACOP members that conflict with the CBA would go through the grievance process outlined in the CBA.”

When ARLnow asked the Board to what degree collective bargaining animated the decision to pull the plug, Garvey said the Board does not comment on internal discussions regarding labor relations.

As for what happens next, Garvey said the Board does not plan on revisiting the powers of the auditor this year.

“Following significant training and preparation, the COB is actively reviewing cases and we want to give the current process time to work before considering further changes and improvements,” she said. “As the COB completes its work, it will provide insights into any challenges and opportunities that may arise in the current process. This will inform consideration of future amendments to the ordinance.”