Drug use intervention programs for youth are in short supply in Arlington County, according to people who help youth with substance dependencies.

The need is particularly acute for younger teens, as the onset of exposure to and abuse of drugs is trending younger, National Capital Treatment and Recovery Clinical Director Pattie Schneeman said in a recent panel.

“‘There’s nothing out there for adolescents.’ I hear it all the time,” says Schneeman, acknowledging that National Capital Treatment and Recovery, formerly Phoenix House, stopped serving children in 2015 because insurance reimbursements did not cover operating costs.

“If you have money, you can send someone to a posh program. You can pay for services,” she continued. “But if you are average, middle-class or a low socioeconomic family, you have no resources, and it is very sad and devastating to our communities.”

Arlington is seeing a rise in youth obtaining and using opioids, with an increasing number overdosing both on and off school grounds — or effectively detoxing in the Northern Virginia Juvenile Detention Center in Alexandria. In some cases, they are prescription, but in many others, they are buying illegally manufactured pills laced with the deadly drug fentanyl, from local gangs or through social media, police say.

The death of 14-year-old student Sergio Flores after a fatal overdose at Wakefield High School has driven teachers, parents and School Board members to call for more action and support from APS and Arlington County. Conversations since then have revealed the barriers throughout the continuum of care to actually treating kids.

For instance, school-based substance abuse counselors can only educate — they cannot provide treatment, according to School Climate Coordinator Chip Bonar, while appropriate treatment options can have a months-long waitlist. The division of the Arlington County Dept. of Human Services that works with children and behavioral health has 43% of its job positions unfilled and acknowledges there are few residential substance use treatment options.

It will be at least two years before VHC Health — formerly Virginia Hospital Center — opens its planned rehab facility. Two years is a long time, however, considering that less than a month passed between the death of Flores and a near-fatal teen overdose Wednesday.

To beef up treatment options, and expand services in the nearer term, Arlington is turning to settlements with manufacturers, distributors and pharmacies it alleges have been key players in the opioid epidemic. Just last week, the Arlington County Board agreed to participate in a proposed settlement against Teva, Allergan, Walmart, Walgreens, CVS and their related corporate entities.

The Board voted to approve the settlement in an unannounced vote at the end of a lengthy meeting.

“This is the latest in a series of settlements that are part of the larger National Opioid Settlement,” said county spokesman Ryan Hudson. “The total funding awarded to the County from these agreements continues to evolve as more settlements are finalized. All opioid settlement funding will be used on approved opioid abatement purposes.”

In the proposed Fiscal Year 2024 budget, Arlington County intends to use money from a previous settlement with McKesson, Cardinal Health, AmerisourceBergen and Janssen Pharmaceuticals to add a therapist to its office-based opioid treatment (OBOT) program.

Arlington will receive a direct payment of $1.6 million through the 2039 fiscal year from the drug distributors and Janssen and, from the Virginia Opioid Abatement Authority, $739,377 through the 2039 fiscal year as well as competitive grants.

“With this new position, we will start serving people 16 and up in the OBOT program, which combines medication with therapy,” said Arlington County Dept. of Human Services spokesman Kurt Larrick. “The new position will double current capacity. The program currently can serve 20 people at once; now we will be able to serve 40 people at once.”

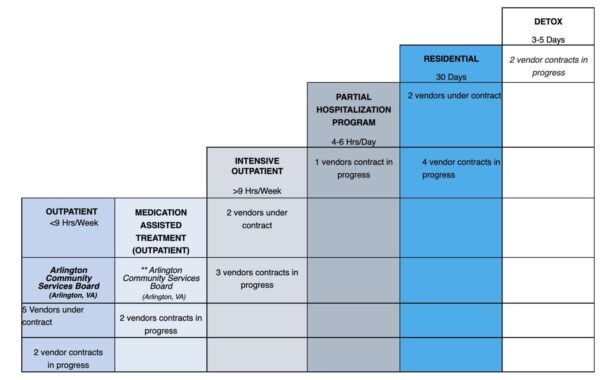

He maintains that there are a number of treatment options for youth, adding that “we are working hard to get the pending contracts finalized to provide more options for care.”

DHS has contracts with two residential treatment vendors in Virginia with another four in the works, he said.

Schneeman emphasized the importance of intervening for even younger children, as the average onset of substance use disorder for patients she sees is now 8-10 years old, compared to 14-15 years old back in the 1990s. It is not just drugs, either. She says she sees adults between 20 and 30 with liver cirrhosis caused by chronic alcoholism.

“We’re going in the wrong direction, as far as I’m concerned,” she said, noting that National Capital Treatment and Recovery has applied to begin working with youth again.

A parent on the panel, who withheld her name for privacy reasons, shared her story of helping her daughter recover from a drug addiction. The abuse problem started in ninth grade and took her in and out of APS. Her daughter, 20, is living in a sober house in Florida, finishing school and going to meetings, she said.

She cannot come back to Arlington because it “is not safe for her.”

“I think I would like to be a cautionary tale,” the mother said, speaking passionately about how recovery requires protective factors like a strong community. “Resources? I have them. They did not cure my daughter. They did not rescue my daughter. I need all of you and you need me, too.”

During the panel, attorney Devanshi Patel, founder of the nonprofit Center for Youth and Family Advocacy, says the roots of the trends seen now include isolation from the pandemic as well as deeper causes like bullying and social media.

“Our children are telling us what they need, and we need to listen,” Patel said in a statement to ARLnow. “We know that there are resource gaps that need to be addressed now.”

“There have been a lot of good conversations happening in our community about how we can collectively meet the needs of all of our children,” she continued. “We must also channel our collective energy to bring forward intervention services now. This will require intentional and meaningful cross-sector collaboration and a youth- centered culture. It also requires bringing kids to the table.”