After months of planning, Arlington County is preparing to enter the first phase of its “Missing Middle Housing Study.”

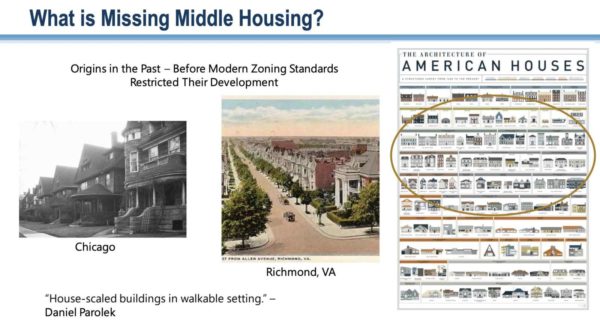

The study will look at whether the county should diversify its housing stock by introducing more housing types that have been typically prohibited from many neighborhoods.

Set to kick off on Oct. 29 after an Oct. 13 orientation meeting for community partners, the study’s first phase will focus primarily on community engagement, as county staff solicit ideas about what housing types to study and key priorities and issues to consider going forward.

The county is seeking “enlisting a network of community partners to facilitate broader study participation through the use of their own communication networks,” according to the study’s website.

“The most important consideration for community engagement is equity and ensuring that access and opportunities to participate in this process are equitable and inclusive,” Arlington County Department of Community Planning, Housing and Development planner Kellie Brown said. “We’re recommending a very distributed community engagement process to make sure that we’re not leaving anyone out.”

As laid out in a presentation to the Arlington County Board on Sept. 23, the Missing Middle Housing Study has been divided into three phases, concluding in the summer of 2022.

With the first phase expected to run until spring 2021, the second phase would start next summer with more in-depth analyses of the different possible housing types. The third phase will turn those recommendations into specific amendments to its zoning ordinance or comprehensive plan if necessary.

Since it was first presented to the public in January, the study’s scope has been slightly modified based on feedback the county got from various commissions and civic associations, as well as an online survey that drew 494 responses, according to Brown.

In addition to emphasizing the need to align Arlington’s land use and zoning policies with its diversity and inclusivity goals, the new scope highlights potential benefits of middle housing, such as improved walkability of neighborhoods and diversity of housing options, and clarifies that the study will be countywide, not just focused on neighborhoods dominated by single-family detached homes.

The refined scope also states that, while the study’s goals are to increase the supply and choice of housing available in Arlington, affordability can be considered as a potential community priority.

The study scope was developed based on community input, but some Arlington residents remain skeptical of the county’s goals, fearing that introducing duplexes, townhouses, and other forms of middle housing to new neighborhoods will further accelerate development in the county without alleviating affordability concerns.

The advocacy group Arlingtonians for Our Sustainable Future argues that the county should not ask residents to weigh in on missing middle housing until it also conducts studies of potential impacts on schools, the environment, flooding, the county budget, and other factors.

“I do think that Housing Arlington has not made the case that we really need to study introducing these housing types,” ASF founder Peter Rousselot said. “We think that it’s going to be good for developers to be able to develop and sell these houses, but without doing these environmental and fiscal impacts, it just doesn’t make sense for us.”

Arlington officials say that changing zoning policies to accommodate housing types other than single-family detached homes and high-rise apartment buildings — like duplexes and townhouses — is necessary to add to the county’s housing supply and manage the impact of anticipated regional growth. It could make up for long-standing policies, such as a rowhouse ban enacted in 1938, that contributed to segregating neighborhoods by race and class.

According to Arlington County senior housing planner Russell Danao-Schroeder, Arlington has only three Census tracts with rental housing that is affordable for Black households that earn a median income, whereas a white household with a median income can find affordable rental housing nearly anywhere in the county.

While this disparity can be partly attributed to income inequality — the median income for black households is $58,878 compared to $134,723 for white households — the close correlation of areas zoned exclusively for single-family detached homes with neighborhoods whose population is at least 70 percent white suggests Arlington’s land use policies also limit access to housing for people of color.

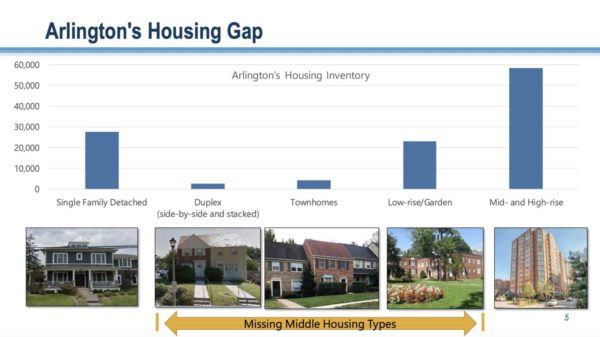

Beyond its potential impact on racial equity, adding middle housing, which currently accounts for only 6 percent of the county’s 116,000 homes, would give more options to residents looking for housing other than the large single-family houses and mid- and high-rise apartments dominating the housing market under existing zoning laws, planners said.

According to the Department of Community Planning, Housing and Development, 91 percent of the residential units produced in Arlington between 2010 and 2019 were apartments, the vast majority of which have one or two bedrooms.

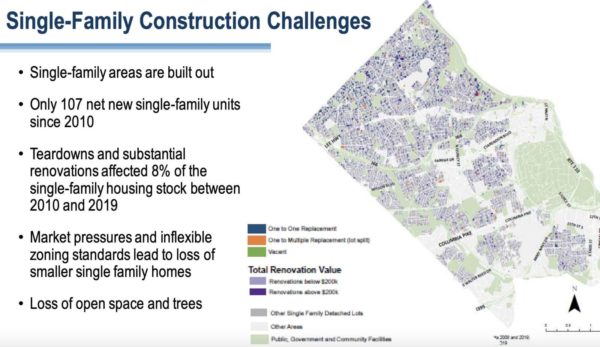

Arlington has produced only 107 new single-family homes since 2010, but 8 percent of the county’s single-family housing stock has been torn down or substantially renovated over the past decade. With 75 percent of the county land zoned for residential uses restricted to single-family detached housing, that means small single-family homes are being replaced with large single-family homes, a trend that county officials say will continue without any policy changes.

“If we are to meet the housing needs of our diverse Arlington community, we must work together to plan for inevitable growth and to correct the past mistakes of exclusionary land use policies,” Arlington County Board Chair Libby Garvey said. “Without changes these policies will exclude ever more people from being able to live in Arlington.”

Photo via Flickr user woodleywonderworks