Editor’s Note: The following article first appeared in the ARLnow Press Club weekend newsletter. Thank you to Press Club members for helping to fund our in-depth local features.

The phone rings on a stormy afternoon in Halls Hill and 92-year-old Hartman Reed swivels in his chair to answer it.

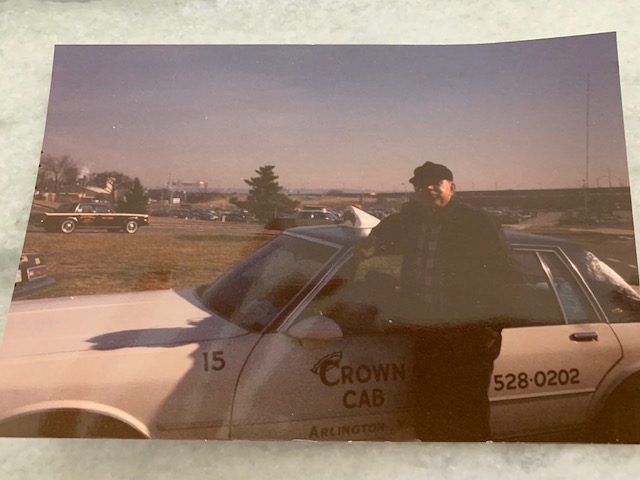

“Hello, Crown Cab,” he says.

Reed first started working for the long-running cab company back in 1958 as one of the first Black cab drivers in Arlington. He picked up customers in a Chevy. Today, more than six decades later, he owns the company, making it one of two Black-owned cab companies in Arlington.

Reed had a second notable job as well. He was also a firefighter at famed Fire Station No. 8 in Halls Hill. It’s believed he was one of the first paid Black firefighters south of the Mason-Dixon line.

“As I grow older, I now know how important it was to be first at things,” Reed tells ARLnow. “I now know what we did made it possible for others behind us to advance.”

For decades, Halls Hill had only a volunteer firefighter department. Even when the county started allocating money to other neighborhoods to pay their first responders in 1940, Arlington declined to do the same for Halls Hill. What’s more, fire companies in surrounding neighborhoods would not come into Halls Hill to provide help.

Finally, in the early 1950s, the county provided money to Halls Hill to hire professional firefighters. Reed, straight out of the Navy, was one of the first hired, starting on the job in 1952 at Fire Station No. 8.

He remains extremely proud of not just the work he and his fellow Halls Hill firefighters did, but the reputation they earned in the community.

“Just because we were Black, we were looked at as people who didn’t have the courage to go in and fight fires,” he says. “We had to prove ourselves. In most cases, I’d say we were outstanding as a company because we wanted to prove that we were as good or better than any other company.”

Fire fighting wasn’t the only community need where Jim Crow reared its ugly head in Arlington in the mid-20th century. In an era there were fewer people had cars, cabs were neighborhood necessities. However, many white-owned Arlington companies would not pick up customers in Arlington’s Black communities like Johnson’s Hill, Halls Hill, and Green Valley.

So, two companies — Friendly Cab Company and Crown Cab — were founded specifically to service those neighborhoods. A number of the cabbies were firemen, including Reed.

In 1958, fellow Fire Station No. 8 firefighter Buster Moten started Crown Cab and hired Reed as his first driver. It’s believed he was one of the first Black cab drivers in Arlington.

For about 16 years, Reed was both a firefighter and a cab driver but he says the two jobs went hand-in-hand. For one, being a cab driver helped him “learn the territory.”

“You have to know where places are when a [fire] call comes in. You can’t be hunting around,” he says. “As a cab driver, you got to know the county a lot better.”

Cabs were also there for emergencies, like hospital visits, particularly since Arlington’s Black residents were often not allowed to go to the hospital closest by.

Marguarite Reed Gooden, Reed’s daughter, remembers her dad picking up mothers going into labor.

“The biggest thing was, at that time, Black women were not allowed… to go to Arlington Hospital, which is Virginia Hospital Center now, to deliver their babies,” Gooden tells ARLnow. “They had to go to D.C., so the cab companies were the main transportation… that got the pregnant woman to D.C.”

In 1974, Reed retired as a firefighter and bought Crown Cab along with his wife. For the next two decades, Reed picked people up and dropped people off across Arlington and the region.

He remembers driving luminaries like Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, TV reporter Dan Rather, and Richard Kiel, the 7-foot-tall actor who played “Jaws” in a number of James Bond movies.

“He came into the cab and had his knees practically up to his chin trying to fit into there,” Reed says, laughing at the memory.

Reed’s favorite thing was that he knew that by the end of the day, he’d have money in his pocket from fares. After retiring from driving cabs in 1992, he moved into more of an administrator role and still owns the company.

Gooden says Crown Cab has continuously provided not just for her family, but those in the Halls Hill community. She explains that her dad grew up very poor in a small town outside of Pittsburgh and made a point to make sure that those around him would never be left wanting. Reed’s careful management of Crown Cab allowed him to give back.

“He’s a giver,” Gooden says, looking at her dad. “And always looked out for family and the community.”

Over the last decade, the advent of rideshare companies like Uber and Lyft have put a squeeze on the traditional cab business. The need to keep up technologically, with apps and dispatching, have forced many companies to shift models or, even, downsize. On top of that, the pandemic even further cut into business.

It’s been a rough go for cab companies, including Crown Cab, over the last few years, even with help from the county.

“When Uber came, we lost about 80% of the value of our company,” says Gooden. “And when the pandemic hit… it was worse.”

But Gooden, Reed, and the rest of the family have a plan. They are working on a ride share-like app for folks to call cabs in much the same way they’d call an Uber and are using Crown Cab’s history, as well as that it is a family-owned operation, in its marketing.

For Gooden, who Reed says is taking over the company, it’s about preserving her family’s history and her dad’s legacy.

“We need to make [Crown Cab] accessible… that’s my goal,” she says. “He wants to leave this as a legacy, so we need to come into the 21st century.”

Reed agrees with his daughter, but also it’s clear that Crown Cab has already helped accomplish what he hoped.

“I just want them to have a much better life than I did as a youngster,” he says.

The phone rings again. Reed excuses himself from the conversation and swivels in his chair to answer it.

“Hello, Crown Cab.”