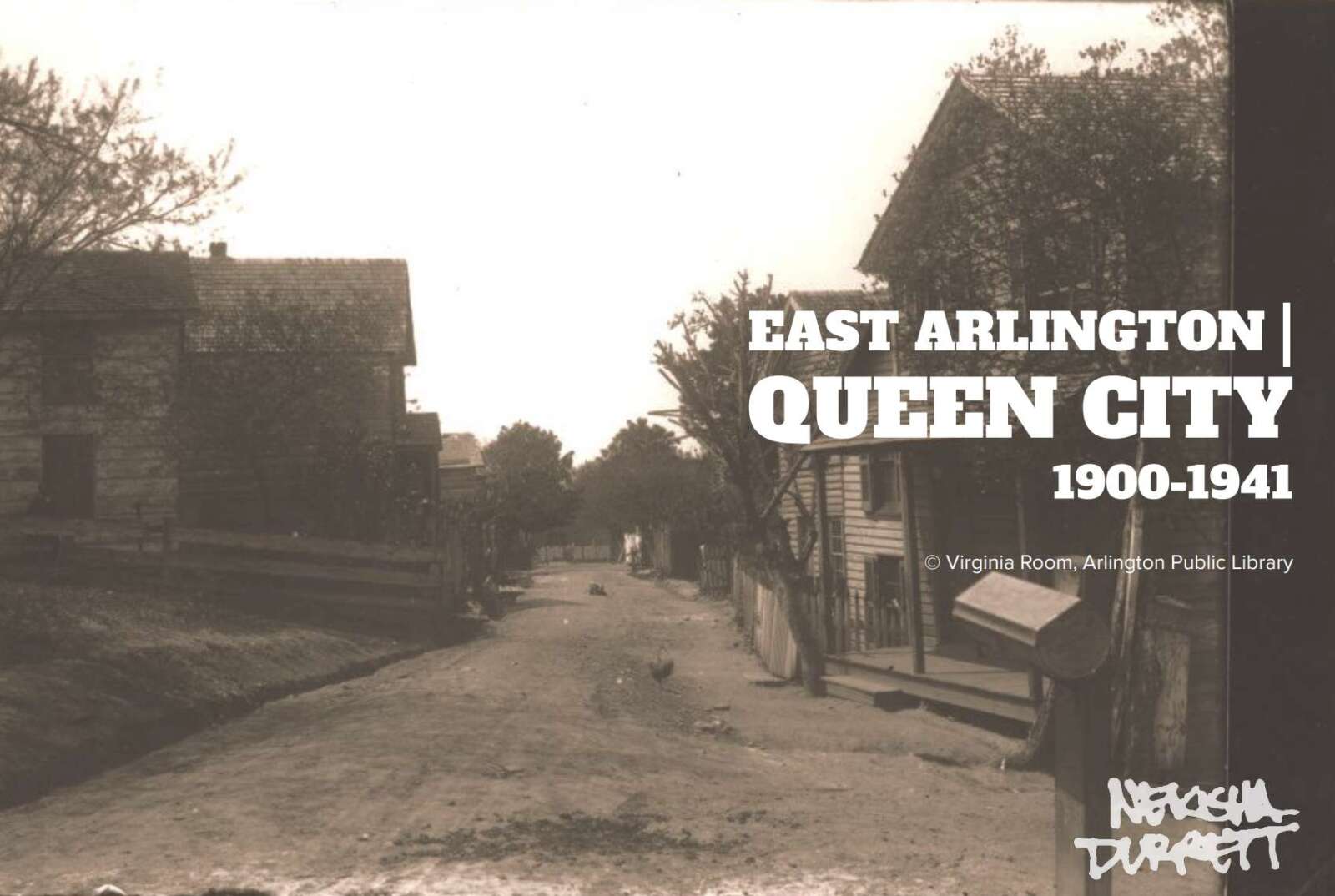

A towering remembrance of the former Black community of Queen City is slated to be included in an Amazon-funded park next to HQ2.

Arlington’s Historical Affairs and Landmark Review Board (HALRB) is set to review the proposed public art installation, from D.C. artist Nekisha Durrett, at its meeting tonight.

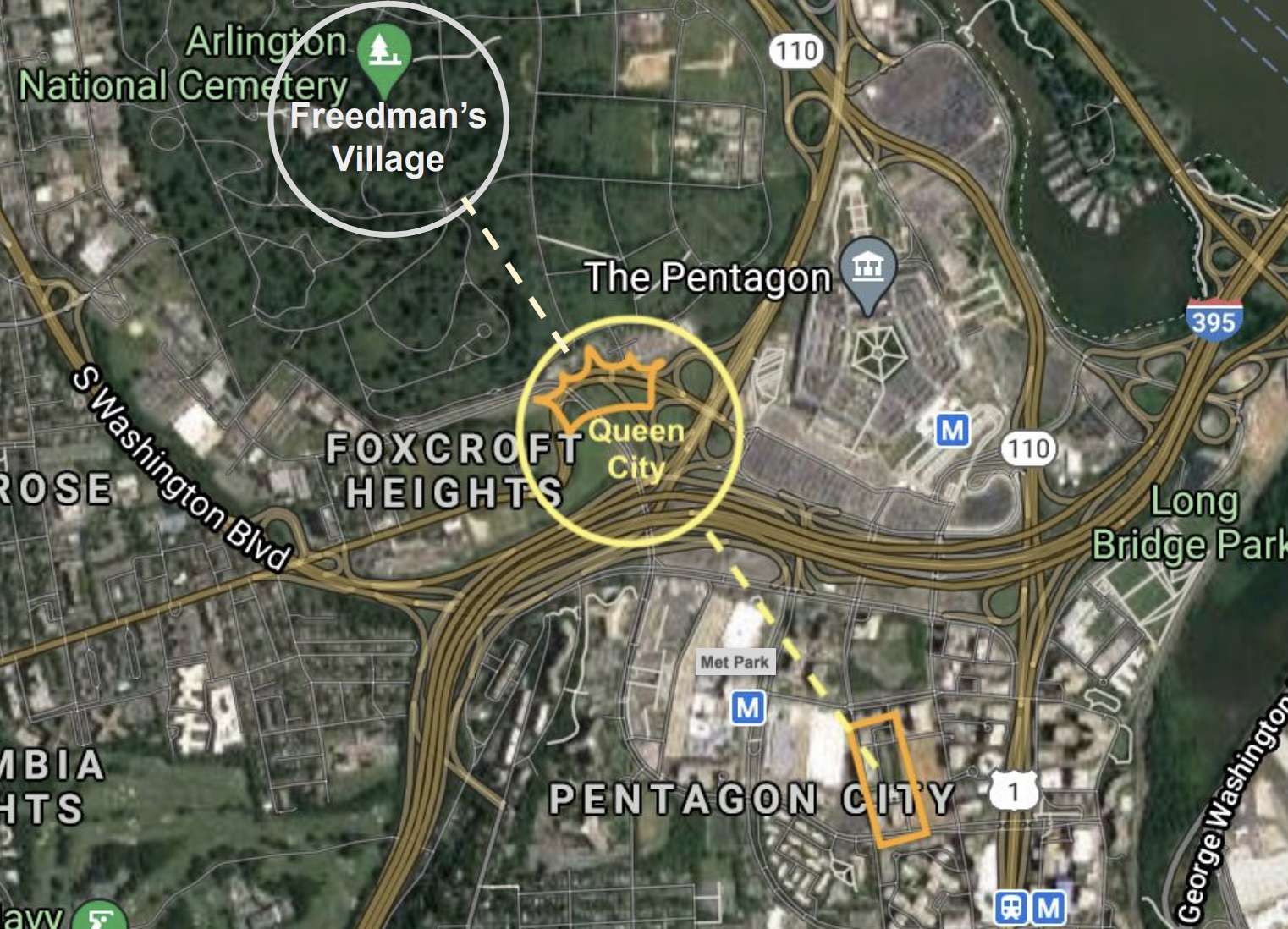

A presentation prepared for the meeting shows a 30 foot tall brick chimney stack, with the words “Queen City” written in brick, along the footpaths of the new Met Park in Pentagon City. The park is currently under construction after the County Board approved a $14 million, Amazon-funded renovation project two years ago.

The revamped park is expected to re-open at some point next year.

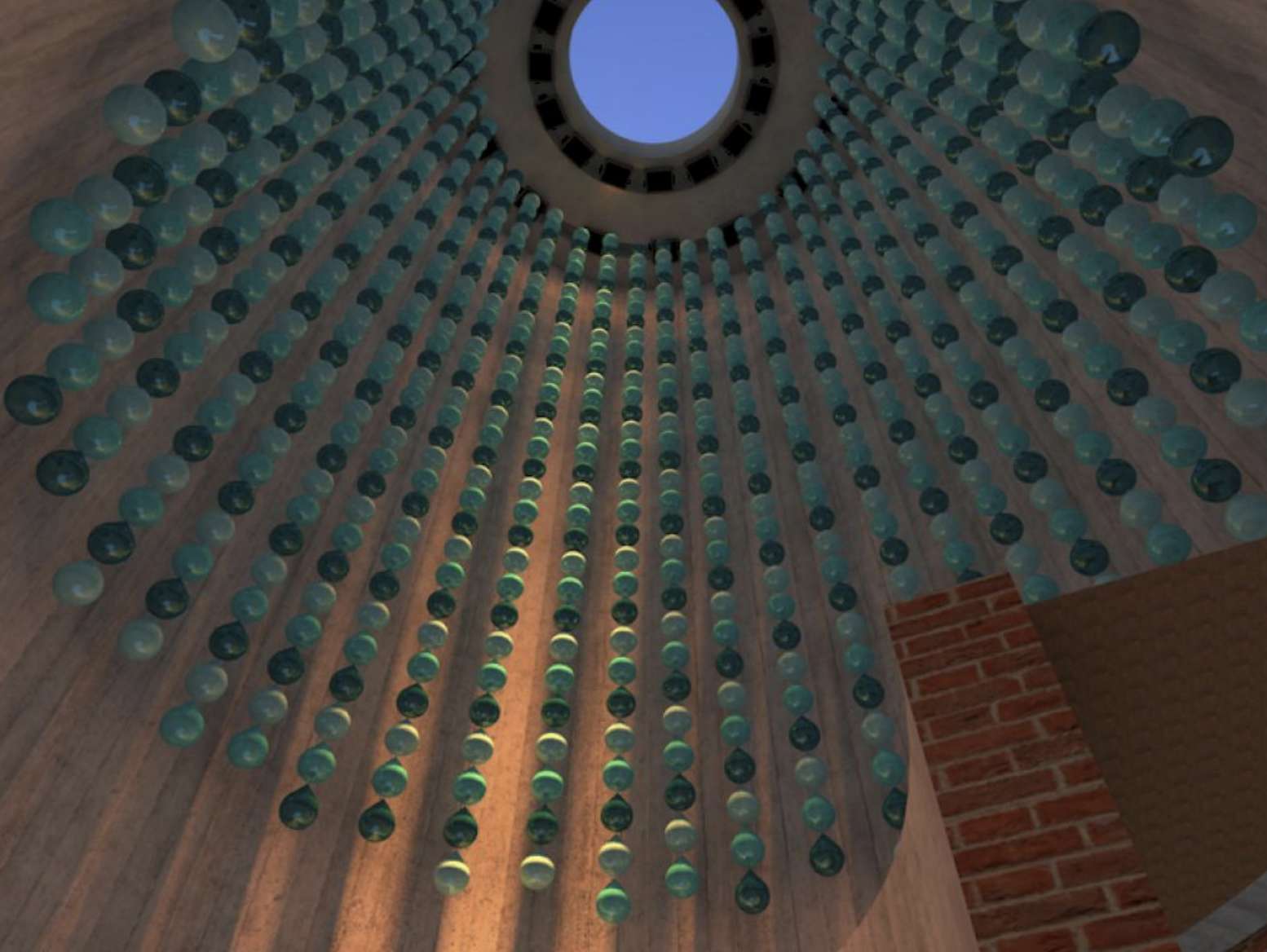

The proposed red brick structure, harkening back to the area’s past as a hub for brick production, will also include a decorative interior that park-goers will be able to freely enter.

Made with reclaimed bricks and illuminated by LED uplighting, the tower will seek to carry forward the legacy of the Black enclaves of Freedman’s Village and, more specifically, Queen City — two of several that dotted Arlington a century or more ago.

Freedman’s Village, founded on the former estate of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee during the Civil War, was closed by the federal government in 1900 and became part of Arlington National Cemetery. Queen City was founded nearby in response to the closure of Freedman’s Village.

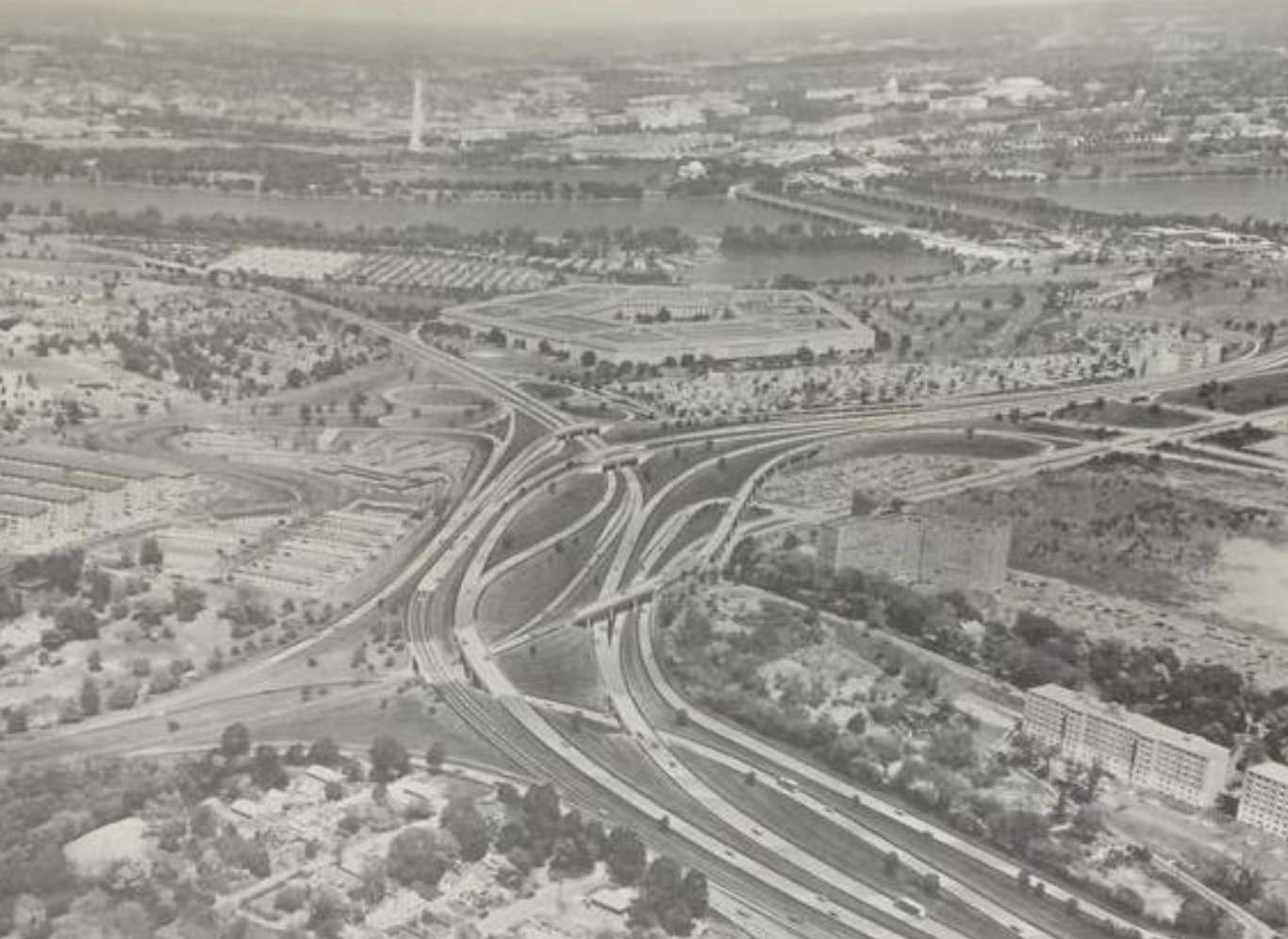

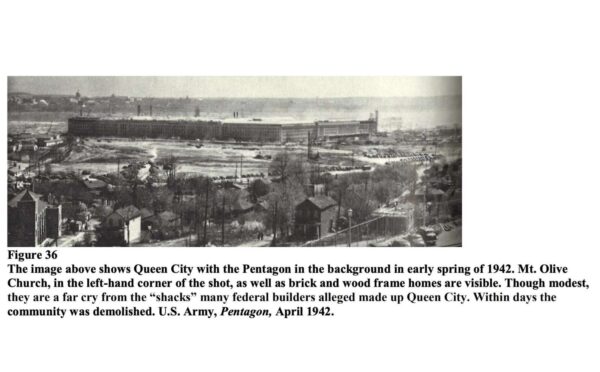

But Queen City, too, would eventually be razed by the federal government — in 1942, to make way for the freeway network built around the newly-constructed Pentagon.

From the doctoral dissertation of Lindsey Bestebreurtje, Ph.D., a curator in the National Museum of African American History and Culture:

Together with the adjacent community of East Arlington, Queen City was located in south-eastern Arlington on flat land, prone to flooding from the nearby Potomac River, near several factories and along the Washington, Alexandria, and Mt. Vernon trolley line. Queen City was built around the Mt. Olive Baptist Church which had roots in Freedman’s Village. Saving one-fourth of an acre for the church, the remaining land was parceled into forty lots to be sold to church members leaving the Village. With small plots of 20 feet by 92 feet, this subdivision transformed the former farm land into a more dense and suburban environment. Many of the homes constructed by former residents of Freedman’s Village at this time were reminiscent of the simple clap-board houses they called home in the Village, making housing type another product of the Village’s diaspora.

By 1942 more than 200 working class families lived in modest but well-kept frame houses. Just as was the case in Freedman’s Village, where residents saw a thriving community, outsiders saw the black neighborhood as a ghetto. In January of 1942 construction began for the Pentagon’s road networks in the path of the communities. Properties were seized through [eminent] domain laws with modest payments. With this loss some community members left the area entirely, while other residents and institutions relocated to Arlington’s remaining black communities of Hall’s Hill, Johnson’s Hill, or Green Valley.

The dissertation notes that the destruction of the Queen City community was personally approved by the president at the time.

“When President Roosevelt came to Arlington to view the site of the future Pentagon building, it was pointed out that though not within the grounds of the building itself, the houses of Queen City would ‘mar the environment of the new building,'” she wrote. “Upon this observation ‘the President said they out to be acquired’ and torn down.”

The construction of the Pentagon also led to the end of brick production in the area.

“But more than homes were lost. Churches, community institutions, and businesses were also demolished,” Bestebreurtje wrote. “Like Queen City, Arlington’s brickyards bordered the Pentagon’s construction site. These yards had long provided Arlington’s black men an option for skilled labor employment beyond the federal government. They were shuttered due to the Pentagon.”

With the new public art, a “trace” of what was lost will stand tall, Durrett’s presentation will suggest.

The HALRB is also scheduled to receive an update on the naming of the park and a second public park, to the north, on the second phase of Amazon’s HQ2.

An online survey and input from local organizations both call for the parks to receive familiar names: Met Park, an abbreviation of the southern park’s former name of Metropolitan Park, and Pen Place, the pre-development name given to the northern HQ2 site well before Amazon’s arrival.