For 64 years, Mario’s Pizza House on Wilson Blvd has served up slices and memories.

From late night pizza runs to Little League baseball, for many Arlingtonians Mario’s has remained one of the only constants in a county where change is the norm. And, according to its current owner Tuhin Ahmed, Mario’s Pizza is not going anywhere, despite some of the change happening around it.

“Mario’s Pizza is going to be here forever,” says Ahmed. “It’s an Arlington institution.”

Howard Levine and his wife, Norma opened Mario’s Pizza House in 1957.

Their son, Alan Levine, tells ARLnow that his dad was a criminal defense attorney but saw a need for a quick bite type of restaurant on Wilson Blvd, which was a very busy road at the time.

“At that time, you didn’t have [Interstate] 66,” says Levine. “So, the main thoroughfare in the D.C. was Wilson Boulevard.”

So, Levine took an old flower shop and converted it to a pizza shop, one that sold ten cent slices.

As to why his father named it Mario’s, Alan laughs.

“Because not many people would have gone to a place called ‘Levine’s Pizza House’ in the 50s.”

Instantly, Mario’s became a community gathering spot. But there was one group that Howard Levine refused to serve.

“The American Nazi Party,” says Alan, of the group led by George Lincoln Rockwell, notoriously had its headquarters nearby. “If they had a swastika, he wasn’t going to serve them.”

Unsurprisingly, the Nazis didn’t take too fondly to a Jewish business owner who refused to serve them but who served slices to the Black community. They protested the pizza shop, holding signs that said things like “Mario the Jew.” But Levine was not intimidated.

“My father was a big son of a bitch,” recalls Alan. “He knew how to handle himself.”

According to Alan, the protest ended when Howard doused the Nazis with a power washer.

Howard and Norma divorced in 1962, says Alan, and his father left the restaurant to his mother as part of the settlement.

“He ran away with the au pair girl,” says Alan, “He ended up crashing a boat in Antigua and staying there forever.”

From that point on and for more than two decades, Norma Levine was the hand at the register exchanging pizza for dollars.

She always worked the register at lunch, Alan says, and that’s how she got to know everyone. When asked if his mother enjoyed the running Mario’s, Alan pauses.

“It supported the family,” he says. “She enjoyed that.”

Thanks to the Levines, Mario’s was a pillar in the community.

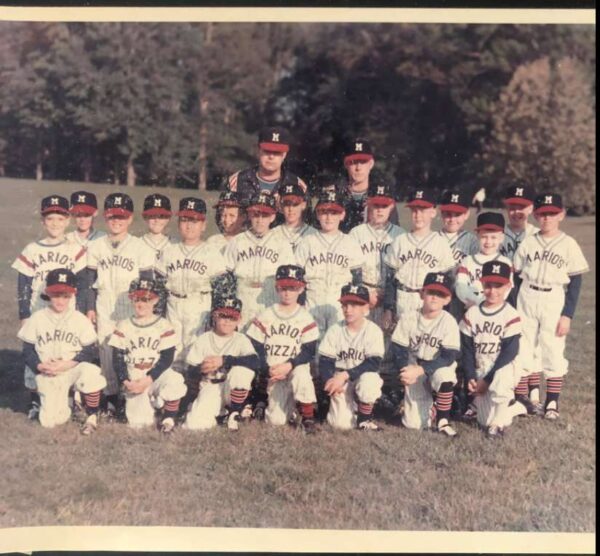

Countless Arlingtonians have memories of Mario’s, from sponsoring Little League teams to the donuts to a miniature golf course with a monkey that bit kids.

“My father [initially] purchased the entire block and there was a miniature golf course where the Highlander is now,” says Levine. “There was a macaw that only cussed and a monkey that [had] a hatred of little girls. [We] had to get rid of the monkey.”

Willie “Lefty” Lindsay started working the grill at Mario’s in 1965 and did so for the next five decades. He only stopped grilling up steak and cheese sandwiches (the most popular thing on the menu, he says) last year, when the pandemic hit.

He remembers Norma Levine as a good boss and someone who was great to the customers.

“She was such a fine person to work around, customers loved her,” 85-year-old Lindsay tells ARLnow. “If you did a good job, she’d reward you for it.”

He believes the key to Mario’s longevity is that the menu and the recipes have hardly changed since it first opened. The customers and the employees have not changed much, either.

Alongside Lindsay for most of those years was Joe Williams, who made the pizza.

Williams worked at Mario’s as well for more than five decades, often side-by-side Lindsay.

“We were like brothers,” says Lindsay. “We never had an argument.”

Williams died in October 2019.

“Joe was an amazing man. He worked seven days a week,” Levine says about Williams. “He never missed a day of work. Except for his wife’s funeral.”

In the mid-1980s, Norma Levine retired and left the restaurant to her kids. She died in 1990. Alan Levine ran day-to-day operations for the next several decades.

“A lot of famous people would come through [to get pizza],” says Levine. “Bill Clinton was a big fan.”

In 2012, Levine put the restaurant up for auction. Four years later, Levine’s former employee Tuhin Ahmed purchased it.

Ahmed started at Mario’s as a delivery driver in 1995. Back then, Mario’s operated 24 hours a day at the time and Ahmed remembers making deliveries three or four in the morning.

On the weekends, Ahmed says, things could get kinda crazy at Mario’s.

“After midnight, when the bars let out, people would keep coming,” says Ahmed. ” Yeah, it’s a mess at the end of the night, because everybody’s throwing trash, everybody’s drunk. But that was the fun of it.”

In 2003, Ahmed had saved enough money delivering pizzas that he approached management about opening a Carvel franchise in the front part of the restaurant.

“Ice cream and pizza go together,” says Ahmed with a chuckle. Fourteen years later, he purchased the rest of the business.

Ahmed says Mario’s remains profitable, despite a rough 2020. “Everybody is now following our model, carry-out and delivery,” he says. “And we’ve had outdoor seating since day one.”

Most importantly, the customers have stayed loyal, he says.

“We can keep going with the same system for the next 64 years,” says Ahmed.

While Arlington continues to change and legacy businesses — like the adjacent Highlander Motel Inn — shutter its doors, Mario’s lives on.

More than the history, it’s how the simple, no-frills pizza shop makes Arlingtonians feel.

“People have felt at home at Mario’s,” says Levine.

“I’ve collected so many [memories] from customers, I’ve put it on our wall at the entrance. Memory lane,” says Ahmed.

Lefty Lindsay might have put it best. He says being part of Mario’s history makes him feel proud.

“I got people now that see me and say ‘Hey Lefty, my dad and my grandad used to come in and get a steak and cheese from you at Mario’s,’ he said proudly. “It’s a good feeling. A real good one.”