The following in-depth local reporting was supported by the ARLnow Press Club. Join to support local journalism and to get an early look at what we’re planning to cover each day.

When a member of Arlington County’s climate change committee took the dais earlier this month, she told the Planning Commission that she had good and bad news.

After evaluating the environmental commitments from JBG Smith for its Americana Hotel redevelopment project, the Climate Change, Energy and Environment Commission (C2E2) gave the project a score of 64.

“Sixty-four is a terrible score but it’s one of the best scores we’ve given,” member Cindy Lewin said.

She commended JBG Smith for participating in national and local programs incentivizing sustainable projects, and, at her request, meeting with a coalition focused on decarbonizing buildings. But, she emphasized, the building will still use significant fossil fuels.

“Arlington County is not going to be able to meet its commitments to climate change, to carbon neutrality and to its [Community Energy Plan] and sustainability goals if we continue to approve so much development,” she said.

Arlington County, which has long been recognized nationally for its commitments to environmental sustainability, is trying to move away from fossil fuels. The burning of such fuels releases carbon into the atmosphere and contributes to a warming planet and other climate changes.

Since resolving in 2019 to neutralize its carbon emissions by 2050, Arlington County has already reached an important milestone toward that goal and knocked out other goals along the way.

In January — two years ahead of schedule — all county operations moved to renewable electricity, mostly because it is buying electricity from a new Dominion solar farm in rural Virginia. Arlington hired a first-ever Climate Policy Officer, purchased electric school buses and published the first edition of a quarterly publication showcasing its climate progress.

“Arlington, in general, is performing very well,” says Arlington County Board Takis Karantonis. “With what we set out to accomplish, we are at a nice level of completion.”

He says going forward, gains will be harder to achieve.

“We will have to electrify transportation and convince people not to drive so much,” he said. “We will have to make sure that new buildings are built at far higher standards than they were before.”

ARLnow spoke with leaders of a half-dozen environmental advocacy groups and every one of them commended the county — but said it is moving slowly and disjointedly toward electrifying everything from county buses to private development projects to single-family homes.

If it moved faster, they say, the county would live up to its reputation and show organizations and individuals these lifestyle and business changes are not only possible but necessary.

“What the scientific community is saying is that we have to cut carbon emissions by 50% by 2030 if we are to avoid going past what we need to to keep temperature rises at a manageable level,” C2E2 Chair Joan McIntyre said. “This is a critical thing we have to move quickly on and there’s a sense that that urgency is not seen in how the county is moving forward.”

These leaders hope the long-awaited climate czar, Climate Policy Officer Carl “Bill” Eger, will have the authority to steer a “whole of county” approach to reaching carbon neutrality. Julie Rosenberg, who leads the Arlington branch of Faith Alliance for Climate Solutions, says she has “ridiculously high expectations” for Eger.

“My hope is that he has staff and brings enthusiasm to decision-making and expectations so that it doesn’t feel like they look up and their bosses are so focused on getting the job done today,” she says. “I was a bureaucrat. It’s hard to run the train and envision a new path ahead but we have to do it. We don’t have a choice.”

In a conversation with ARLnow, Eger said some siloing is inevitable in local government but many divisions of Arlington’s government are working to solve problems collaboratively. His vision for a “whole of county” approach goes beyond the headquarters at 2100 Clarendon Blvd.

“As we look to the future, we are looking at a ‘whole of community’ thinking,” he said. “The county is the trusted institution standing behind the foundation of the work, bringing up community foundations, neighborhood groups, institutions, nonprofits and universities, to bring together resources and creativity, ways of problem solving and embedded intelligence to work toward contributing to solving climate change.”

He says his first aim is to integrate climate into policy conversations the way the county evaluates equity in its major policy discussions so it remains top-of-mind for the government.

Resolutions and roadblocks

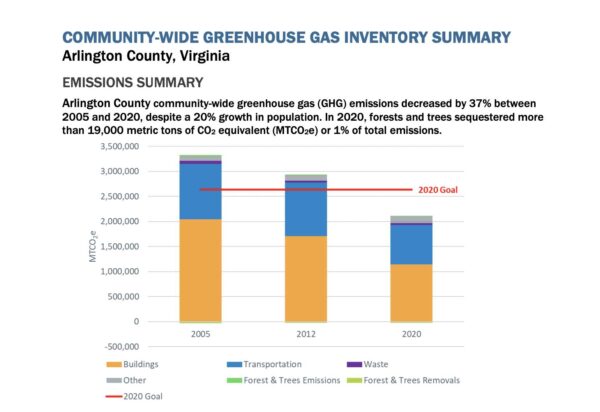

Arlington has been working to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions for years and has made significant strides since 2005. Over the last decade, it adopted several climate-oriented resolutions with plans to support its efforts.

A division of the county’s sustainability office, Arlington’s Initiative to ReThink Energy, keeps close track of the county’s progress on short, medium and long-term goals toward carbon neutrality. So far, Arlington has accomplished 95% of the goals it set out to achieve in one to two years.

But environmentalists say some of these goals are low-hanging fruit compared to the much bigger issues the county is promising to solve in the future. In the meantime, it is continuing to allow new, fossil fuel-reliant construction.

“Every one of these very large, new, high-rise multifamily buildings that is going in with centralized gas-powered hot water systems and HVAC systems, they’re going to be a challenge to electrify,” says John Bloom, the chair of the Potomac River Group of the Virginia chapter of the Sierra Club. “It can be done, and it will have to be done, but we’re creating more challenges with every new building we put in with gas infrastructure.”

Arlington already rewards developers that build “greener” buildings with greater density through a program that has yielded some 19.3 million square feet of more sustainable construction.

One developer that participates says it is an effective program and electrification is not the only way to decarbonize.

“Electrification can be seen as a ‘fuel switch’ — replacing natural gas with electricity,” Kimberly Pexton, Senior Vice President of Sustainability at JBG Smith, said in a statement to ARLnow. “Electrification will temporarily increase the carbon footprint of a building until the grid also removes fossil fuels from the power generation puzzle.”

Large, multifamily buildings, like those it is building in Crystal City and Pentagon City, present a challenge for electrification.

“While the technology may be available, the application is not currently viable for all shapes and sizes of buildings,” she said.

JBG Smith instead focuses its sustainability efforts on building in Metro-served areas, reducing carbon in building materials and during construction, and ensuring buildings are designed to significantly reduce energy and water use, she said.

Looking forward, it is watching a development that could make lighting systems more efficient: power over Ethernet, which transmits both electricity and data over copper wires.

While individual buildings might not be carbon neutral, Karantonis says development is headed in the right direction.

“We have to accelerate but we don’t want to kill economic development, either,” he said. “We need investments in infrastructure, parks… stormwater… all this requires significant fiscal response. For this, we need to design our programs in a way that the decision-makers right now, especially in the development world, buy in and come along.”

Bloom says there are other ways the entire county can run on electricity by 2035.

“One of the most promising is community choice aggregation,” he said. “Virginia law allows a jurisdiction to become its own power provider and buy electricity from all kinds of providers. It’s a break on Dominion’s monopoly over our supply. That is something we should seriously be considering in Arlington.”

Another issue the advocates bring up is the timeline for transitioning the Arlington Transit bus fleet to electric buses.

The county says it is moving as fast as it can. It will be buying four battery electric buses that will serve as a pilot when the new Arlington Transit Operations and Maintenance Facility in Green Valley opens in the first quarter of 2025. The facility will have infrastructure for charging 63 buses.

The next year, it is set to test out fuel cell electric buses, leaving 12 years to make its fleet fully electric.

“The sooner we start, the less behind we’ll be. We do have to take the plunge,” says Elenor Hodges, the executive director of EcoAction Arlington. “Everything we put in place that’s still a fossil fuel bus or site plan… we’re that much further from our goals.”

Eger confirmed that he has heard these kinds of frustrations in the few weeks he’s been on the job.

Electrifying buildings or installing electric vehicle charging infrastructure is easier said than done due to a nationwide shortage of electricians with the know-how to, for instance, install and maintain electric heat pumps.

“This work is extraordinarily hard,” Eger said.

Standing up solutions for the community

County staff is mostly occupied with reducing carbon emissions of the government but this is only 4% to 5% of Arlington’s total emissions.

“The other 95% is measured by our ability to get individual Arlingtonians to enlist in the list of actions that will reduce their carbon footprint,” says Karantonis. “It requires a complete departure nowadays from almost a century dominated by fossil fuels and the lifestyle that comes with that.”

That can range from reducing consumption and waste to choosing to take public transit, or walk or bike. One of the biggest emitters for people, however, can still be their home and it takes a lot of forethought to rely on renewable electricity for appliances and heating and cooling, says McIntyre.

“As a homeowner, I know it’s challenging to figure out what to do to electrify your home,” she said. “I’ve got a 100-year-old home. It can be daunting.”

The county’s AIRE division educates people on how to do so using federal incentives, like those in the Inflation Reduction Act, or by going solar through a county cooperative program that has helped 656 homes as of 2022 install solar systems.

There is also work to do to ensure less advantaged people use these resources, too. For Rosenberg, closing the “climate equity” gap is a big priority for Faith Alliance for Climate Solutions.

Research suggests economically disadvantaged people pay more for their electricity and live in less energy efficient homes, with poor insulation and inefficient HVAC systems, she said.

“There’s outstanding research in the last couple of years that perfectly overlays [hotter neighborhoods] and red-lined places,” she continued. “That heat has a huge impact on their quality of life.”

There is a lot for Arlington County and its residents to do and many eyes watching, says Lewin, citing the construction of Amazon’s second headquarters in Pentagon City. (Amazon’s buildings will be powered 100% by renewable electricity from Dominion’s solar farm in Pittsylvania County.)

“It’d be wonderful if we could be a national model and lead the way to an all electric future,” she said. “I hope we can figure out a way to work together to an all electric future.”