(Updated 10:30 a.m.) Where the prosaic golden arches of the stand-alone McDonald’s once perched, a residential high-rise now joins the many skyscrapers defining Rosslyn’s changing skyline.

Some old landmarks have been incorporated into new high-rises, including the McDonald’s now beneath Central Place Tower on N. Lynn Street and the former Fire Station 10 at the base of The Highlands.

Others, such as Tom Sarris’ Orleans House, a fixture for nearly 50 years, were replaced with offices and a newer generation of businesses like Compass Coffee and Cava.

Although commercial office buildings have been a constant feature of Rosslyn’s skyline over the past 40 years, the last decade has seen a shift towards more living space.

Anthony Fusarelli, Arlington County’s planning director, says that out of the approximately 8 million square feet of new development planned in Rosslyn, nearly half is designated for residential use. Office space accounts for roughly 2.8 million square feet, retail occupies 171,459 square feet, and the remaining space is allocated for hotels.

The transformation reflects a broader shift the county undertook over the last 20 years to steer urban planning toward residential and mixed-use development to accommodate a growing population, boost economic activity and adapt to people’s waning enthusiasm for the conventional workplace.

This trend is likely to persist, not only because of changes in work patterns post-pandemic, but also because Arlington County is encouraging residential development in Metro-oriented Rosslyn to help address its reported shortage of housing supply.

Planning Rosslyn’s future

To understand how and why this shift occurred, Fusarelli pointed to Rosslyn’s history.

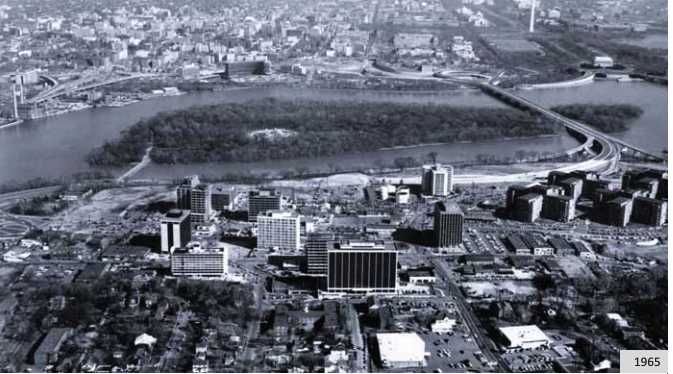

Sixty years ago, if someone had ascended the 555-foot Washington Monument and looked westward across the Potomac River, they would have seen a very different Rosslyn. The view would have been dominated by rail yards, pawnshops, oil storage tanks and other retail and industrial operations.

“So, just this mix of varied uses that is quite different from what we have today,” Fusarelli said.

After World War II, Fusarelli said the Arlington County Board recognized the area was valuable because of its proximity to D.C. Eager to establish Rosslyn as an auxiliary office hub for the growing federal government, the county embarked on an aggressive campaign to transform the area into a vibrant business district.

“Back in the early ’60s, Arlington established a new zoning tool called the ‘site plan process,’ which incentivized private landowners to build much taller buildings, much bigger buildings, in exchange for providing certain public benefits,” Fusarelli said.

Rosslyn quickly became a hub of 10 to 12-story office buildings.

Local elected leaders soon discovered the drawbacks “to having areas that are predominantly or almost exclusively single use,” says Fusarelli.

“One of the downsides is outside of the business hours of 9 to 5, life on the street could often be pretty limited and sometimes referred to as a ghost town,” he said.

Rosslyn’s residential rise

Realizing its mistake, the county spent the next 30 years going through several iterations of planning to re-imagine the Rosslyn-Ballston Corridor, devising strategies to add more apartments over ground-floor retail.

In the last decade, residential skyscrapers exceeding 300 feet — such as the residential tower at Central Place, the former Holiday Inn, and The Highlands — have sprouted up.

There’s more on the way.

There are several other mostly residential mixed-use developments in the pipeline, including the plans to convert the former Ames Center office building and RCA building.

Mary-Claire Burick, president of the Rosslyn Business Improvement District (BID), said this will add more than 1,000 apartments. She says the BID is projecting at least $4 billion in new development over the next few years.

“The fact that we’re located in Virginia, which is a very business-friendly state, obviously, is another draw, but really, it also comes down to lifestyle,” Burick told ARLnow.

“We’ve got green open spaces, improved pedestrian infrastructure, great public areas that are alive with activities and amenities like restaurants and retail,” she continued. “All these things, when you sort of pull them together, that’s really what both residents and businesses are looking for.”

The county is pushing for mixed-use development both to see economic growth, and thus more tax revenue, but also to address the region’s housing shortage. Fusarelli says this a challenge the county has “not kept up with.”

A high-density housing fix

Between 2010 and 2021, Arlington’s population grew by about 15%, according to 2020 U.S. Census data, adding approximately 31,000 new residents.

Despite dipping slightly in 2021, the county still faces elevated housing demand, which it aims to alleviate with transit-oriented development and 2-6 unit Missing Middle housing types in districts previously zoned for single-family homes.

Local housing expert Emily Hamilton believes apartment projects near Metro stations — the kind Rosslyn provides in spades — will drive local housing growth more than Missing Middle-type construction.

“In terms of housing abundance and affordability, multifamily will continue to be a very important contributor to Arlington County,” says Hamilton, the co-director of the Urbanity Project at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

“On the transportation side, traffic counts are actually going down on some of the county’s important arterials relative to what they were in the ’90s,” she added.

Infill Friday.

A McDonald's turns into a McDonald's + 377 apartments in Rosslyn. pic.twitter.com/k7SCERXcx3

— Emily Hamilton (@ebwhamilton) August 12, 2023

Moreover, Hamilton says Arlington County’s decision to zone apartments near transit saved it from more severe housing shortages seen in other high-income coastal regions, even those with robust transit.

“It’s a low bar, but when we look at at California cities or Boston or New York, the D.C. region is more affordable, and also, our quality of housing is is generally higher,” Hamilton said.

For instance, the New York City suburbs of Westchester County or Long Island have trains to downtown job centers but only allow low-density, commercial buildings near transit, she said.

According to the 2015 county-approved Rosslyn Sector Plan, Rosslyn is projected to add 3,000 new housing units by 2040, with the capacity to accommodate up to 5,000 new units and 8,000 new residents.

So far, Fusarelli says about 3,609 housing units have been approved or are under construction. That makes up more than half of the roughly 5,800 units built across Arlington in the last five years, as stated in a recent county report.

Multifamily housing remains in demand in Arlington. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau shows that the apartment vacancy rate in Arlington earlier this year stood at 5.4% — lower than both the statewide rental vacancy rate of 5.9% and the national rate of 6.4%.

Fusarelli and Burick agree the post-pandemic uncertainty around where and how people choose to work is fueling the move from new office buildings to mixed-use development.

But Burick is confident Rosslyn’s business environment remains “as robust as ever,” especially as office owners adapt to workplace trends by doubling down on amenities and renovations to entice employees back.

“I think what has transformed and changed over the years is the recognition that the way people live and work in the 21st century is not just about work… people just commuting into the office and then home. That’s not consistent with what people want to do nowadays,” she said.