A year into new stormwater requirements for single-family home projects, homebuilders and remodelers say even the improved process is laborious and expensive, costing homeowners extra money.

On the other hand, Arlington County says that permit review times have shortened and that the program will be evaluated for possible improvements.

Before September 2021, builders had to demonstrate that a given property had ways to reduce pollution in stormwater runoff to comply with state regulations aimed at cleaning up the Chesapeake Bay.

Last year, the county began requiring projects that disturb at least 2,500 square feet of land to demonstrate the redeveloped property can retain at least 3 inches of stormwater during flash flooding events through features such as tanks, planters and permeable paver driveways. Builders must also refurbish the soil with soils that increase water retention.

Arlington Dept. of Environmental Services spokesman Peter Golkin says improvements like these “are vital as we continue the work toward a flood resilient Arlington,” especially as “the pace of single family home construction in Arlington remains strong.”

But the regulations are fairly new and could change, Golkin said.

“The first projects in LDA 2.0 are now coming to construction, and the County is entering the phase of evaluation to identify potential adjustments and improvements,” he said. ”The County expects to have more information about any LDA 2.0 updates by mid-2023.”

The updates were intended to address increasing infill development and rainfall intensity, and the downstream effects of runoff and impacts to the county’s aging storm drains and local streams.

Builders and remodelers say the changes have caused new headaches and resulted in projects shrinking in size.

“It only gets more complicated, costs more, and takes longer,” says architect Trip DeFalco.

Andrew Moore, president of Arlington Designer Homes, said he’s avoided this process in many projects after telling the clients about the potential costs and permitting time.

“People are motivated to think, do I need that bump-out to be 14 feet? I can live with 12 feet,” he said. “It saves you $50,000 and 3 months.”

Despite the hassle, permit applications are still coming in at a clip of, on average, 20 per month.

Responding to redevelopment

In the wake of the destructive July 2019 flash flood, residents has discussed and voted on ways to address stormwater mitigation in Arlington, while the county has put more funding toward stormwater improvement projects.

The issue of runoff has figured into debates about how to protect streams and the impacts of allowing the construction of two- to eight-unit “Missing Middle” houses in Arlington, though such projects could only occupy the footprint currently allowed for single-family homes on a given property.

In the wake of the flash flooding, the county introduced new regulations for what it says is one of the biggest runoff contributors: new single-family homes.

“Ensuring more robust control of runoff from new single family homes, which create the majority of new impervious area from regulated development activity, remains a top County priority as part of the comprehensive Flood Resilient Arlington initiative,” Golkin said.

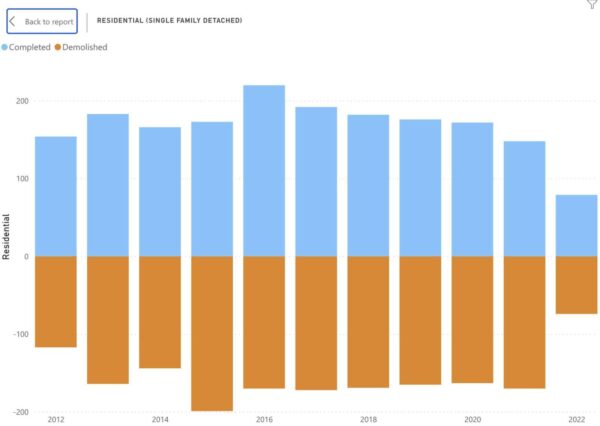

An average of 167 single-family homes have been built and an average of 155 torn down annually over the last 11 years, according to Arlington’s development tracker tool. Demolitions peaked in 2015 and completed projects in 2016.

A past of pollution

DeFalco, who spent a few years as a builder, too, says the “county’s hands are a little bit tied” on this issue because they have to meet state requirements aimed at curbing pollution in the Chesapeake Bay.

Runoff brought fertilizer into the bay, causing algae and plants to grow quickly and then die, sink to the bottom, where they decayed and used up oxygen, says civil engineer Roger Bohr.

“The state is pushing on the county and the federal government is pushing on the state,” DeFalco said. “But the implementation on the homeowner level is pretty onerous… I don’t think the residents have any idea what’s going in their side yards.”

Golkin compared the transition period right now to when new state stormwater management requirements took effect in 2014.

“Staff and the building and engineering community ultimately came up to speed,” he said.

What happens to homeowners

Any land that will be built on, paved over, regraded or driven over by work vehicles counts as “disturbed.” Projects under 2,000 square feet don’t need a permit, while projects between 2,000 and 2,499 square feet need a surveyor to certify their size.

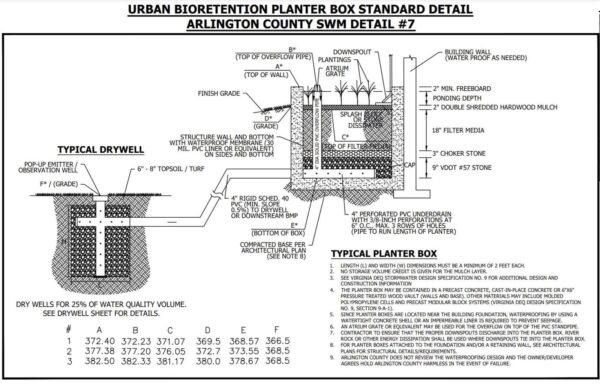

Disturbed area can quickly add up to 2,500 square feet. Moore is building a 400-square-foot addition that is subject to the new requirements, and will need three dry wells, two stormwater planters and a detention tank.

“For me, it’s the cost of doing business,” he said. “For you, who wants to build a house, that’s real money for something that has to be inspected every other year and requires maintenance.”

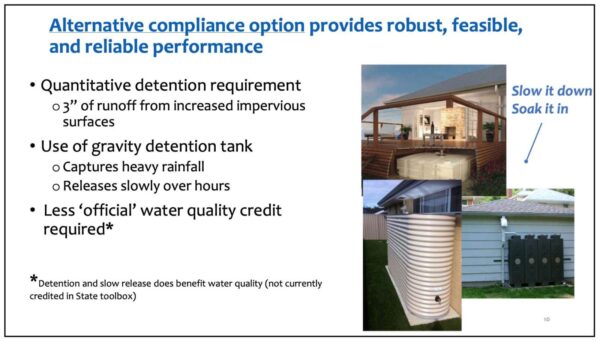

Ahead of the change in requirements, DES said LDA 2.0 would shorten permitting time. The program includes simplified calculations for designing detention tanks, as well as two tracks intended to be “less onerous” and streamlined.

Builders say that hasn’t been their experience. Golkin, however, says review periods have dropped overall.

“The time to complete the initial review for all LDA projects has decreased from 35-40 days in early 2019 down to 25-30 days more recently,” he said. “There was a major spike in LDA permit submissions (62 single family home applications in September 2021) prior to LDA 2.0 taking effect that month, which impacted plan review times last fall.”

How it works

Under LDA 2.0 requirements, when it rains multiple systems kick into gear to reduce the amount of runoff at the heaviest point of the storm. The retention system has many parts because a little grass has to work double-time to absorb water running off of a house.

About a quarter of the runoff will go into a tank on the property, which holds water for 48 hours, Bohr said.

The rest goes into a planter box or a dry well in the ground, and is slowly released via a “pop-up emitter,” he said. Eventually, the water infiltrates back into the ground or evaporates.

Some of these systems can be aesthetically pleasing, like planters, but above-ground cisterns are ugly, according to Bohr.

“These tanks are big, ugly plastic tanks,” he said. “We haven’t had too much push back because everyone’s resigned themselves to they have to do what they gotta do.”

Golkin says there’s a “learning process” for choosing a tank and figuring out how to integrate it into the project’s design.

“Staff have been working closely with builders and their contractors to provide guidance during construction of the first projects now underway,” he said.